Marianne Hirsch

Monika Weiss’ Nirbhaya

by Marianne Hirsch

included in Panel 5: Nirbhaya - Monuments & Memory, which took place on Friday, May 7, 2021 as part of the international symposium Monument|Anti-Monument organized by CEL Centre for Architecture + Design St Louis, moderated by Rick Bell and hosted by CEL’s director Jasmin Aber. Composed of 6 panels, the symposium was inspired by the work of Polish artist Monika Weiss and her forthcoming public project Nirbhaya. Panel 5 included Lance Jay Brown, Marianne Hirsch, Wendy Evans Joseph, Krzysztof Wodiczko, James E. Young, and the artist.

Monika Weiss’ Nirbhaya responds to an emergency—the emergency of rampant acts of violence suffered by women and by other marginalized groups across the globe. How is this an emergency, you might ask, when this violence has been so thoroughly normalized as to remain unmarked and quickly forgotten -- if it is noted at all.

Gender and race-based persecution and injustice are part of the social fabric of slow violence and compounded trauma we have learned to live with. The consequences of this self-blinding and oblivion have emerged with special virulence this last year – in the radically differential effects of the Covid pandemic on different populations, for example, in the aftermath of the release of the video that recorded the brutal murder of George Floyd last summer, and in the exponential growth of the #MeToo movement around the conviction of Harvey Weinstein in early 2020.

Once in a while, a spectacular case produces what Walter Benjamin terms a “flash of recognition” that makes it impossible to continue looking away and forgetting. In focusing public attention on everyday violence, these singular stories have the potential to raise awareness, generate conversation, mobilize resistance, and effect change. Such was the case, for example, with the catastrophic rape and murder of Jyoti Singh in New Delhi in 2012. But what happens when the memorialization of everyday violence is occasioned by a singular monumental event, focused on one case or one individual? (there are a number of examples, of course-- George Floyd and Breona Taylor, Parkland and Columbine)

There is necessarily a tension between individual and familial trauma, on the one hand, and the endemic and systemic injustice for which the individual comes to serve as a signifier and symbol, on the other. The emergency to which Monika Weiss’ Monument/Anti-Monument responds also lies here – not only in the horrific rape and murder to which Jyoti Singh was subjected, but also in the impossibility of marking and memorializing gender-based violence in a way that addresses: its pervasiveness, our general oblivion to it, and the disappearance of the individual victim beneath her outsized symbolic role. How can an act of what Monika Weiss calls unforgetting do justice to these different dimensions of compounded violation?

Jyoti Singh fought back, she bit her attackers. Indian law forbids the disclosure of the rape victim’s name and so she became—Nirbhaya—the fearless one. Does this mean she was not afraid? Or that the public actually needed her to remain anonymous and fearless in order to be able to bear witness to and to protest this horrific crime? What happens to her, to her story, when we ask her to become such a symbol? How then can her story – now elevated to the level of myth—call attention to less spectacular but no less traumatizing everyday acts of rape and gender violence? How does it help us unforget them?

In many cases of spectacular violence, the legal system fails. But it didn’t in Jyoti Singh’s case: the perpetrators were punished—three were hanged. We might ask what such punishment actually accomplishes, whether it doesn’t actually exonerate everyday rapists, by giving the illusion that the problem is being dealt with on a grand scale. But even though this case produced accountability, even though successful legal victories were gained and are making women’s lives safer in India, so much more awareness, activism and change are needed. Here is where art, memory and monument come in. What kind of art work can mobilize awareness and mass resistance to rape, enable unforgetting and repair, and allow us to imagine a future when everyday acts of gender-based violence are no longer tolerated?

Monika Weiss’ work rests on the belief that a monument can do what the law can’t, that it can mobilize memory and affect change. It’s a belief I fully share. In the spirit of this shared commitment, I’d like to make a few comments and raise a few questions about some of the aesthetic choices of Nirbhaya: Monument/Anti-Monument and about how they help or possibly impede these urgently important goals.

First, the title, Nirbhaya. I wanted to think about the choice of this particular Indian case as an inspiration for the work, and about its title – given the fact that the work is not meant to be specifically about India or Jyoti Singh, but about gender violence more generally and globally. Using India Gate as a monument to invoke and to contest all at the same time, enables the artistic allusion to the heroization of war and empire and, indeed, to the connection between these toxic masculine enterprises and the victimization of women.

By laying the India Gate on the ground and rejecting verticality, the work not only rejects this heroization, but also makes visible this connection between rape and war. And yet, I wonder about how this all works when the monument is built, not in India, but in Poland and the US. Nirbhaya is untranslatable, it is foreign, and this, risks relegating the crime to another place and time, to a not here, or to a timeless nowhere. That might be right, of course, the emergency is not tied to any one place, it is global. And, yet, untranslatablity risks mystification. And, as I mentioned, I am also troubled by the attribution of fearlessness to the raped woman and would love to hear more from Monika about this choice.

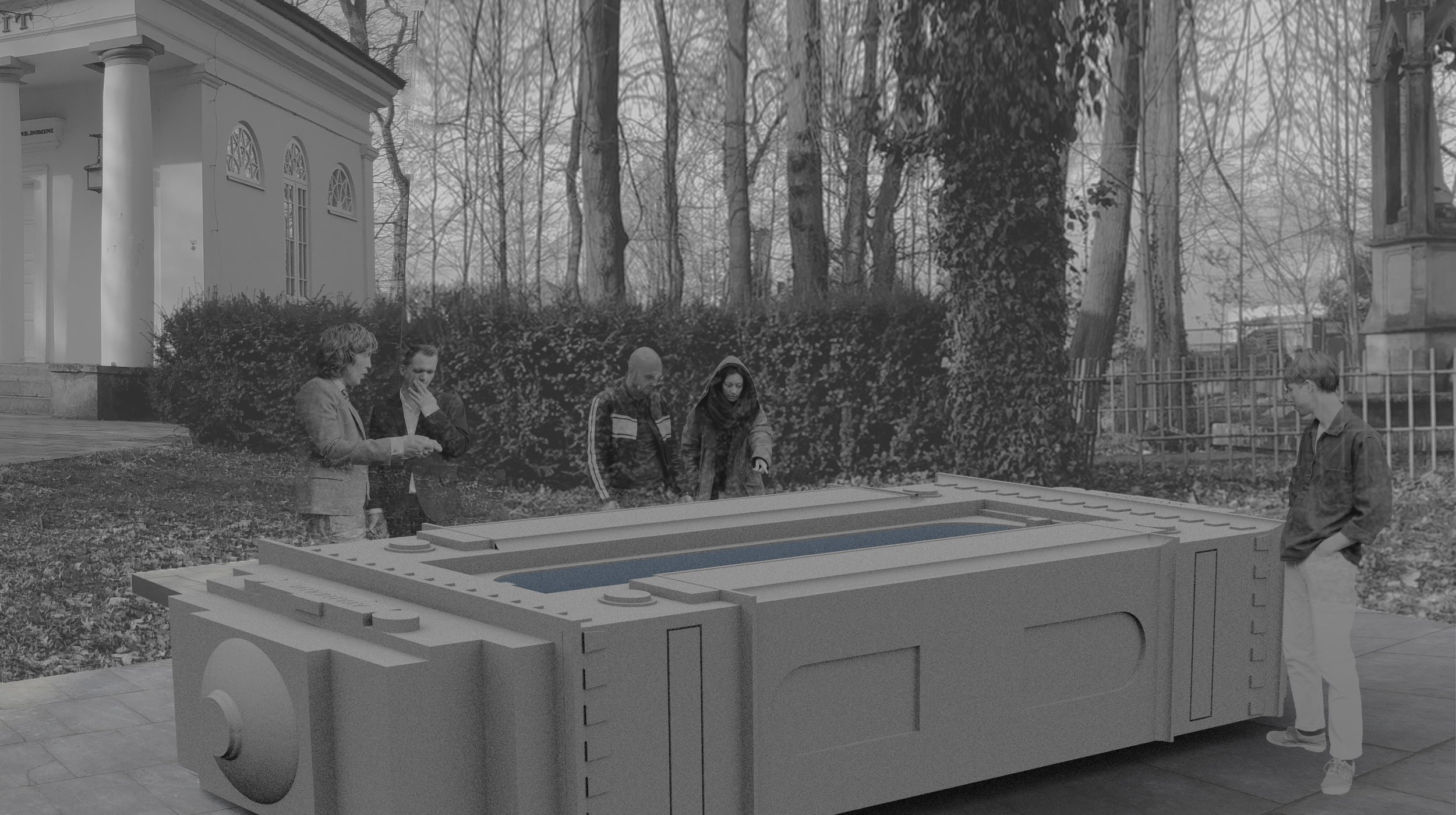

Second, the two-part subtitle title. Admittedly, Nirbhaya is not an anti-monument, it is a monument/anti-monument. How so? It is, of course, anti the monumental India Gate and the imperialism and nationalism it celebrates. Thus, it questions the monument itself as a vehicle of inclusive, reparative memory work. At the same time, it is also a monument—large, formidable, permanent.

I’ve been trying to think of other examples of monuments to rape and gender violence. All the ones I can think of are fleeting installations or exhibits, often communal, participatory and temporary works. I’m thinking, for example, of Patricia Cronin’s Shrine for Girls in the chapel of St Gallo at the 2015 Venice Biennale, where, on the three altars of the desacralized chapel, the artist installed girls’ clothing she collected in three sites of rampant gender-based violence—dresses from the Magdalene Laundries in England, hijabs from the victims of Boko Haram in Nigeria, and Indian saris. Metonymically connected to the violated bodies, these clothing items function both as relics and as traces, as a kind of skin connecting the viewer to the victims and the crimes.

The 2015 installation Thinking of You in Pristina, Kosovo is more local and specific. Here the artist Alketa Xhafa-Mripa collected dresses from women around the country to memorialize the more than 20,000 Albanian victims of rape during the Serbian invasion of Kosovo. She installed these dresses in the Pristina football stadium, thus radically re-signifying the space. Participatory projects such as this one enable women to let go or shame and fear, to come forward and admit to being violated or to admitting that their mothers or daughters were the victims of rape and war. Or take the REDdress project, the collaborative work of indigenous Canadian artist Jaimie Black, a member of the Métis community, calling attention to the 1,200 Aboriginal Canadian women murdered or gone missing between 1980 and the project’s first installation in 2011. Black collected red dresses from women in the community and hung them in various public sites in Canada and the U.S. to call attention to the disproportionate violence affecting women in indigenous communities. And as a last example, the artist Vahit Tuna who installed 440 pairs of high-heeled women’s shoes on two walls in Istanbul’s Kabataş neighborhood to mark the 440 femicides perpetrated in Turkey in 2018.

These projects and other similar ones are more fragile, contingent and fleeting, perhaps less monumental than Nirbhaya but Nirbhayaalso shares some of this contingency in the projections and metamorphoses that are an integral part of the project.

And yet, all these projects share the same dilemma. They all want to bring the violated women forward, they want to foster a circle of solidarity and protection around them. Most important, they want to call attention to the magnitude of a crime, even while focusing on the singularity of each individual case – each dress, each pair of shoes, each name is one victim and these works want to do justice to each of them. They each approach these goals in very different ways.

And here is where the slash between Monument and Anti-Monument in the subtitle of Monika Weiss’ work seems to me to be a particularly apt proposition – if not solution. Nirbhaya is not a monument but it’s also not not a monument. It’s not an anti-monument, but it’s also not not an anti-monument.

I’d love the panel to help me think some more about that slash—and about the work that it does in addressing the emergency of memorializing the everyday acts and effects of gender violence.

Marianne Hirsch, New York, 2021

Marianne Hirsch is the William Peterfield Trent Professor of English and Comparative Literature at Columbia University and Professor in the Institute for Research on Women, Gender, and Sexuality. Hirsch’s work combines feminist theory with memory studies, particularly the transmission of memories of violence across generations. Her recent books include The Generation of Postmemory: Writing and Visual Culture After the Holocaust (Columbia University Press, 2012), Ghosts of Home: The Afterlife of Czernowitz in Jewish Memory, co-authored with Leo Spitzer (University of California Press, 2010), Rites of Return: Diaspora, Poetics and the Politics of Memory, co-edited with Nancy K. Miller (Columbia University Press, 2011). Marianne Hirsch is the former editor of PMLA and the recipient of fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation, the ACLS, the Mary Ingraham Bunting Institute, the National Humanities Center, and the Bellagio and Bogliasco Foundations. She is one of the founders of Columbia’s Center for the Study of Social Difference, and its global initiative “Women Creating Change.”