Aneta Szyłak

Your trap shall be your shelter: The hidden desires and public appearances of Monika Weiss

by Aneta Szyłak

in Monika Weiss: Five Rivers, Lehman College Art Gallery, City University of New York, and Galerie Samuel Lallouz, Montréal, 2007

There is a state of mind which is almost impossible to describe and which can rather only be individually experienced: the state of the highest brightness and consciousness when at the same time the external bodily features do not seem to express this. Immersed in the internal world, the brain is producing phantoms and floating thoughts liberated from being formulated or shared. It directs the human being into the space either on the edge of or even outside social entanglements.

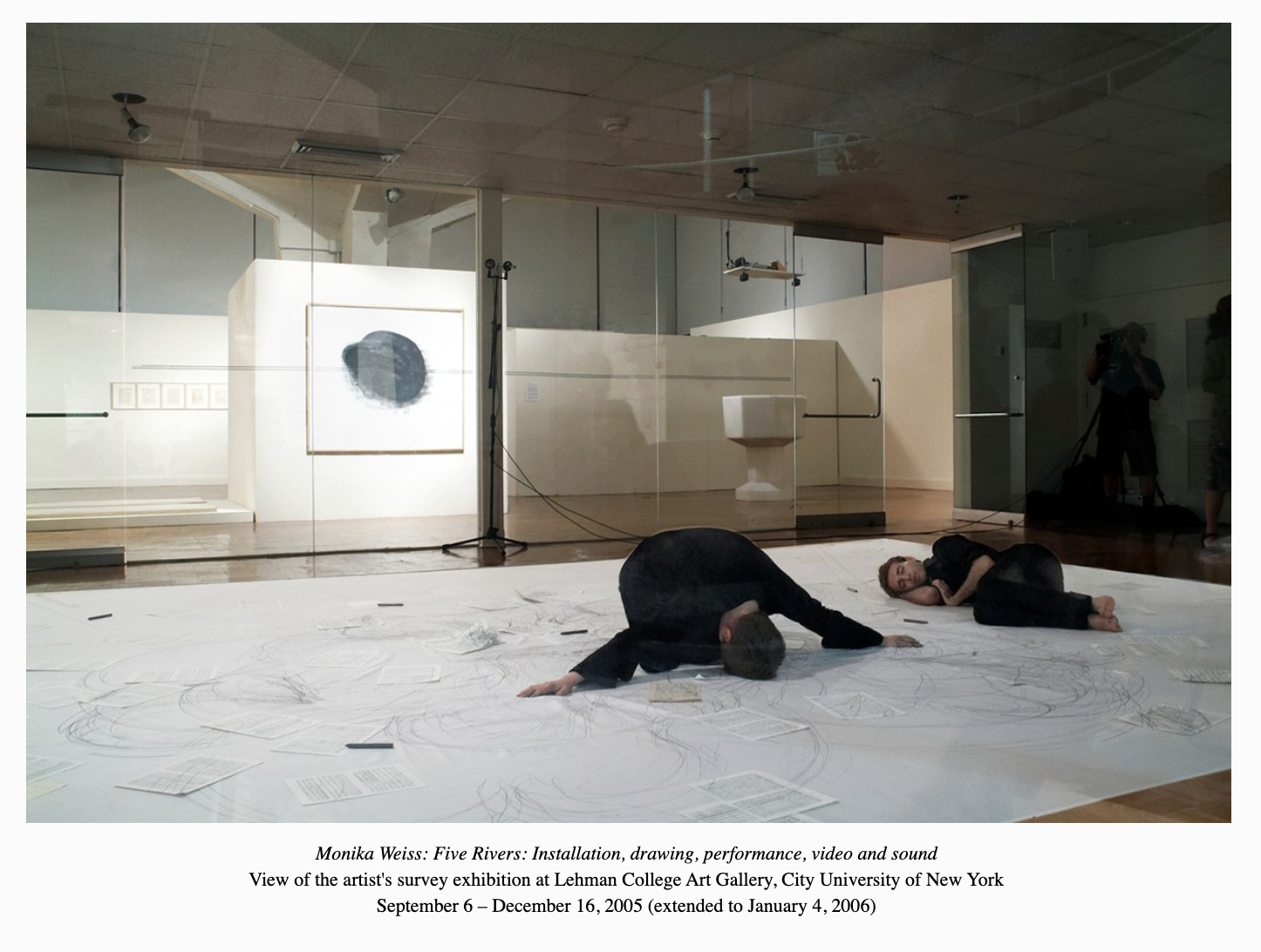

In a conversation we had just a few months ago, Monika Weiss said, "The boundary between presence and absence is very fluid." [1] Her practice is - almost entirely - dedicated to the very expression of this position, through repetitive and monotonous performance. This meticulous perseverance and extension in time allows us to face and partly experience this very verge of awareness and aloofness, the situation of being here and being there. If time could be wounded, the space for this kind of existence would rest in this wound: the wound of the profound split between calmness and anxiety, between longing and chosen loneliness, between unexpressed desire and staged public appearance.

Asking myself about the most important features of Monika Weiss's art, I understood that its core is based on finding her own mode to display the performing body and art as a process, while maintaining a mixture of methods of representation and documentation. There are several, overlapping and inter-textually corresponding, layers of how the body is exposed and represented. It is a very specific going or - according to its features - crawling from the mobile to the frozen state of the body and back again.

Extremely personal, even intimate, the art of Monika Weiss strikes us by the way it merges performance, drawing and sculpture as well as sound and media art. Here, the more traditional artistic forms merge with those that appeared later and expand the notion of the artist's body, its representation and medialisation. The way the artist approaches the idea of the performing body in the gallery space and outside of it and the way she integrates drawing into the performative art and the media creates strong relationships between all the constituents. In a conversation with Nathalie Anglès, Weiss once saidM

"My works consist of elements that come both from past and from present, bringing evidence of action, bearing traces, visual or virtual, of something that has happened. In that sense both drawings and installations are performative." [2]

It seems to be formative for her practice to maintain different time paths and systems of recordings to approach the generally unsubstantial features of ephemeral work. Her performances have no dramaturgical plot; there is no key moment or spectacular finale. It seems to be a practice for its own sake, gaining and losing its intensity throughout time. The presence of the viewer is not always required: the artist refers in her talks to the situation, when the public had already gone and she was found in a chalice by the gallery employees, no less astonished by the situation than she herself. She provides herself and the audience with separated and dissimilar encounters. The one related to her own experience is based more on sensing through the body and the tactile, haptic component plays the significant role. The one of the viewer is more connected with perception through the eyes and ears and the general relation with the space. Weiss's works, depending on their specificity, can be understood as the miniatures of social relations and the dramatic moments of loneliness. The struggle between public appearances and private rituals reveals here, its subtlety and complexity.

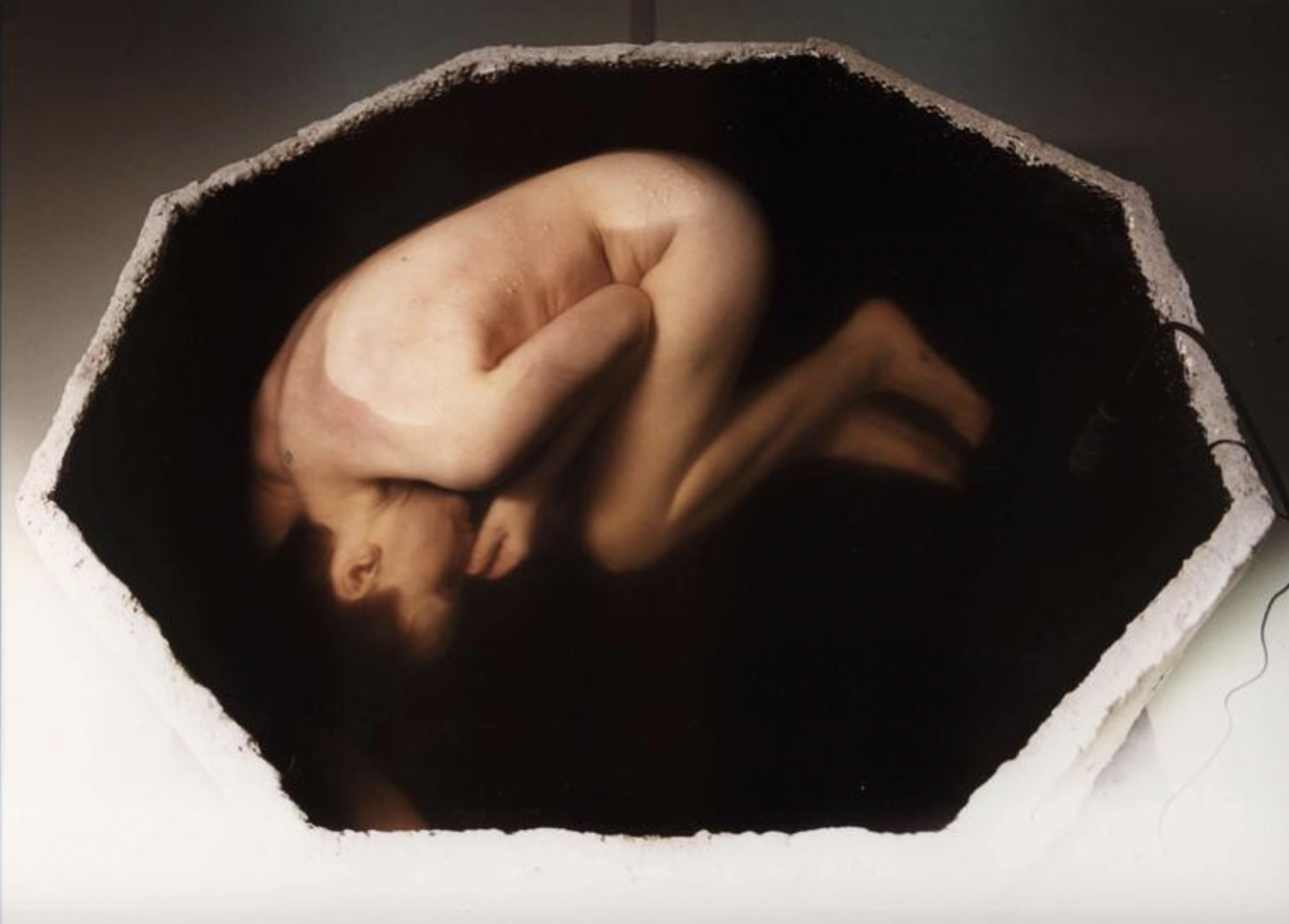

There are some durable elements that make Monika Weiss's performative practice recognisable. There is the artist's body, often naked or dressed in a very modest, minimalist way, crawling or curled-up. Then, there is a space or its specific limitations, provided either by a simple plane of paper or fabric or by the sides of a shelter especially built for the body. So, there is a container: chalice, vessel, sarcophagus, and here is its filling: liquid paint, water or paper. It is a space of her own, made from the need for a visibly defined area. Making such a space connects her art with early feminist practices searching for a suitable arena to express subjectivity, as in the writings of Virginia Woolf, whose definition of the workspace for the female creative being lies in the core of the feminist system of production and representation.

The other component of Weiss's work is the outline she draws around her body, both visible and invisible. This activity reminds us of the early conceptual gestures of Ewa Partum, the Berlin- based Polish artist, whose 1965 works, such as Presence, were the first to approach the subject of the space for the female and feminist artist. As Angelika Stepken puts it, "Ewa Partum spreads a primed, unpainted, un-stretched canvas on the ground. Then she lies on this surface and traces the contours of her body." [3] Where is the space for art and for the artist, Partum seemed to ask. What is left for her presence?

The very matter of being there seems to be a formative constituent part of Weiss's artistic practice: the here and now of the subject, the momentum of appearance, the long-lost Benjaminian aura through its contemplative aspect and the immediacy of its impact on the viewer. This understanding of the spatial features of artistic practice seems to be internalised by Monika Weiss in a very conscious way. It accustoms the feminist awareness of the spatial conditions of artistic production but its core rests in both the conceptual gesture and the existential understanding of corporeality.

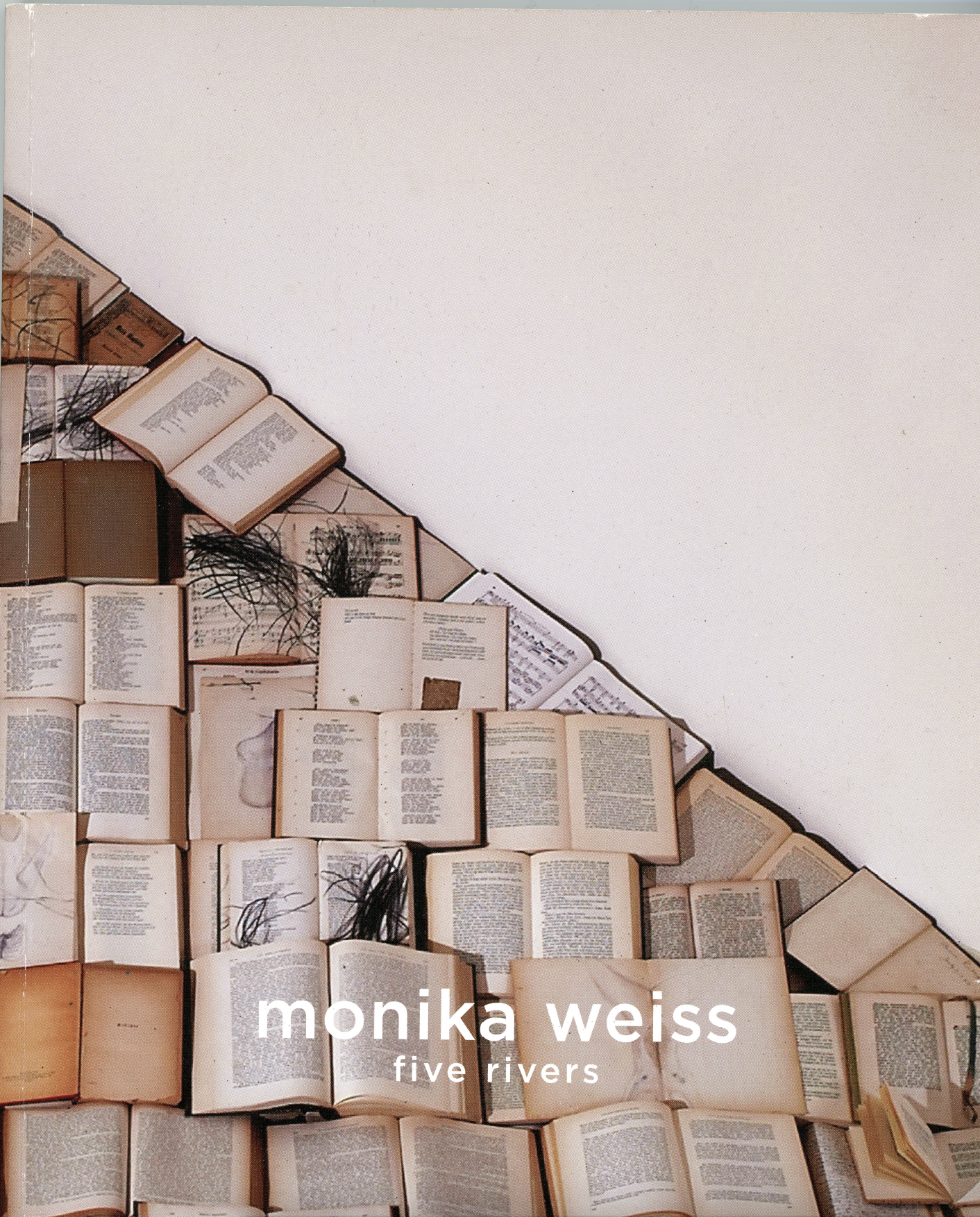

The situation changes when she performs on a prism of books in her installation Phlegeton-Milczenie in Germany. Carving through the layered Logos, through rational, masculine, language-based cultural experience, Weiss, unlike in any other of her works, draws a strong link to the locality, to the context of German literature and to the damage to intellectual discourse done by the Nazis before and during WW II. The meaning of the title, connected with notions such as the unexplored, unspoken, unnamed and intuitive, was strengthened by the accompanying sound consisting of vocal parts and also of the sound of burning paper. But her understanding of paper, especially old paper, as a reference to human skin, makes us also think about the internalisation of culture, about the absorbance of the intellectual through the bodily experience.

Some works of Monika Weiss might be interpreted - through their relationship with the given location - as performative installations whereas some others appear to be still performances, suspended or extended in time, facilitating the very definition of space. Her practice brings back the once-forgotten notion of the temple to the gallery space, understood as defined by obsessive ritual, a compulsively re-enacted activity, when at the same time making it very private, intimate and nearly fully internalised. Some of her works put the viewer into the position of the passive spectator of a clandestine celebration, whilst others engage the audience, inviting it into sharing and togetherness.

Born and given an artistic education in Poland, Weiss seems to have some distinguished predecessors - besides Ewa Partum - among the female artists in her native country. The fragility in seeing the human body as a shell or vessel seems to be inherited from the oeuvre of Alina Szapocznikow, who, through her resin-cast sculptures, said more about human existence than any other female artist before and not many after. The prematurely deceased, eminent representative of the 1960s, Szapocznikow is now seen as an ancestress of today's feminist Polish artists, the first to touch in such a deeply existential way the issues of death and mortality, female sexuality and the body. Her expression of the feminine form as well as the idea of the body as a vessel rests in the origin of female subjectivity in Polish art. The most memorable examples are the Fetish series and Tumeurs.

But the way in which the body is represented in Szapocznikow art differs from that of Weiss. Szapocznikow always sculpted the fragmented body, turning its moulded elements into separate objects. Weiss represents the female body both in her performances and in her drawings as a rounded, full form exposing its vulnerable openings. But what both artists have in common is the specific aesthetisation of the body. In the words of Piotr Piotrowski, writing about Szapocznikow, "Form [...] allows her to maintain intimacy without falling into vulgarity; it allows the silence and the subtlety of the message to be maintained [...]." [4]

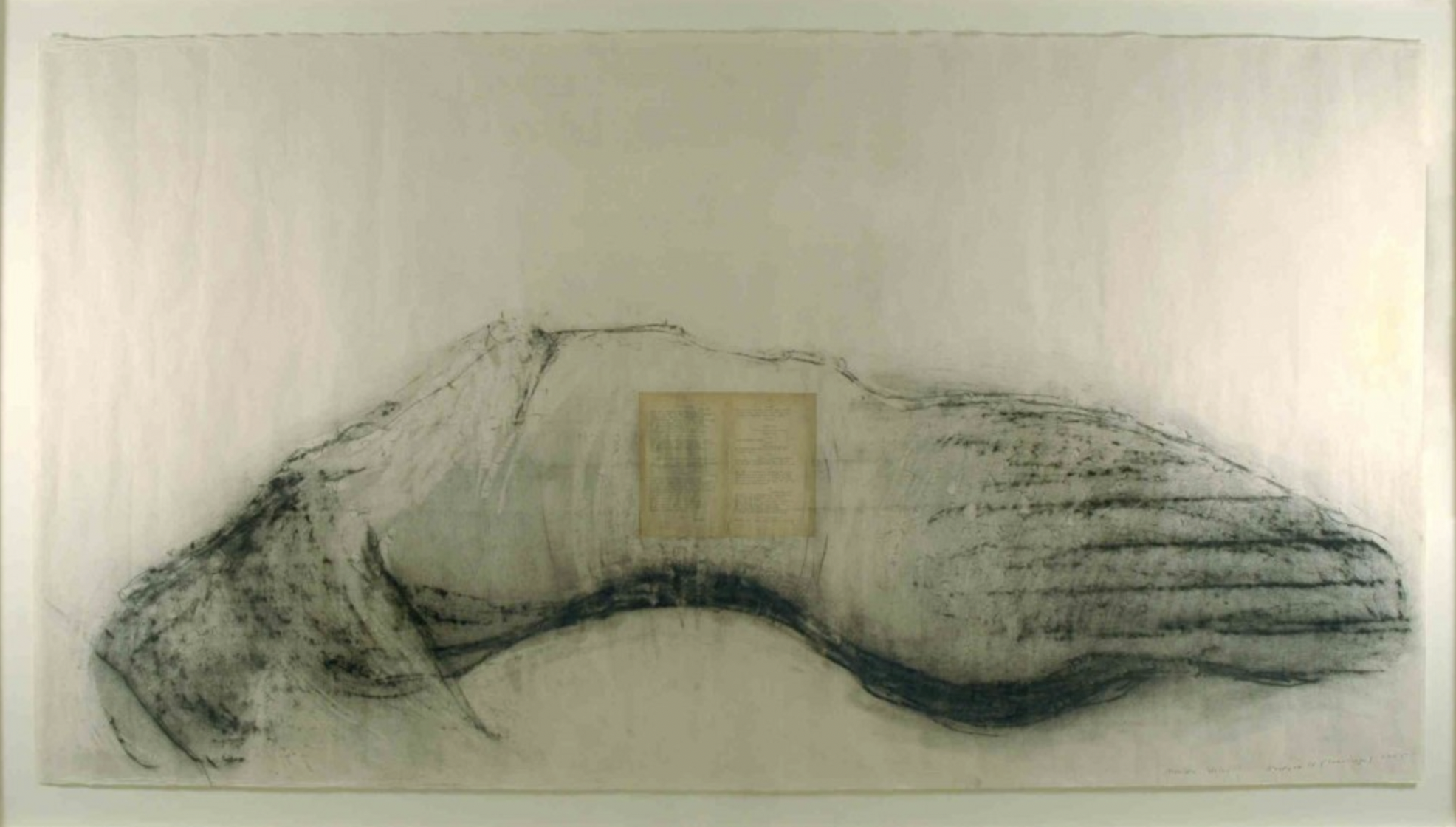

The forms recollecting the female body in works by Polish women artists appear in the 1970s. In the almost abstract early textile works by Magdalena Abakanowicz, e.g. Read Abakan (around 1970), the soft intersections of woven objects remain those of female openings. Rebirth and fertility are addressed in Monika Weiss's drawings, such as Pandora's Belly or Ennoia (Bird) (both from 2000). According to the artist, "The figures presented frontally open themselves to the gaze, sometimes having their belly open like a flower, with a symbolic representation of the inner organs, or their legs up with a view of the vagina opening."

The drawing can also be spread out on a table, making the female body in the picture even more vulnerable. Both the curled-up body within a chalice and that in her drawings seem to the viewer to resemble submissive sexual positions. Although the artist quite openly rejects obvious erotic connotations in an understanding of her art and treats the body rather as an instrument of an artistic message, the carrier of meaning rather than as a body with all its fleshy and biological connotations. The sexual message here appears to be unclear, undefined, its addressee cannot be discovered, but it is extremely striking in the way it combines submissive innocence and mature openness.

There are ink drawings by the artist in relation to the ink-leaking body in her performance work. The body opens up, shows itself as vulnerable and fragile, and risks being the subject of rapturous dominance. The ink pouring from the body, from even the smallest pore of the skin, not only during the performance but also for weeks after its effecting, expands this feeling of weakness, vulnerability and dependence whilst maintaining a profound physical connection between the body and the world.

The passive body seems to express hidden needs and unspoken desires. It builds an ambiguous relationship with the viewer. It invites the spectator to voyeurism and at the same time makes him or her aware that the viewer can also be watched. It expands the notion of desire so strongly connected with the history of art, making us think of what desires the object of desire and where this carefully planned and executed passivity is coming from, reminding us of the questions raised by the early videos by Lili Dojourie. If during the performance the artist makes unexpected eye-contact, it is not aggressive or confrontational, it is inviting, although it might create some kind of confusion and uncertainty.

The works of Weiss express feelings both of being hidden and of being captured. The body is lonely, penetrated by the ritual liquids. The dripping of these liquids from the female body, leaving her own traces in the gallery space, reminds us of those that appear in relation to the natural fluids in such performative acts as those by Anna Mendieta or the sculptures of Kiki Smith. "Fluids have no boundaries and as such they connote the lack of boundaries between the self, the body and the world," [5] notes the artist.

The ceremonial, ritual and performative components and references to natural elements link Monika Weiss with Teresa Murak. This Polish artist, whose career started in the 1970s, realised several works combining naturally grown shoots, architectural components, public the space and the body. Murak’s performance works consisted of the element of immersion in water, in her case infused with freshly-grown shoots. Murak used to grow different kinds of shoots on gowns she later wore and on household towels, but her rituals of growth and fertility appear to come through the complete acceptance of the female role and its parallel to the natural processes in the life of plants and the sequence of seasons. Weiss though seems more to have focused on an individual experience approach and is more aware of the impact of the camera image of the body.

There are multiple perspectives in looking at the artist's body in her work - directly, from above or from the side, or the way it is being captured by the video camera and through the way it is drawn on the paper. Sometimes in real time, sometimes with a time delay. The medialised image of the body in Polish female artists' work appeared strongly in the works from the 1990s by Izabella Gustowska, where the camera and monitor work as a looking-glass, mirroring the female face and a passive silhouette. Also in works, such as Floating (1997) or The Source (1995), water is an important constitutive component and has an almost symbolic and mythic dimension - here we can see some subtle link. Gustowska though is rather addressing the mind in the state of dreaming whereas Weiss appears to be more there if not yet awakened.

Through her recordings or the parallel projections accompanying the performances, Monika Weiss creates corresponding situations, extremely personal, exploring the alter-ego and its possible representation. The Self seems to be in the very centre of her practice although here it is connected with anonymity and image production. Weiss is apt to see herself as a mirrored image of a universal human being. In strongly addressing the issue of the human condition, the work of Weiss brings to mind T. S. Eliot's "The Hollow Men":

Between the desire

And the spasm

Between the potency

And the existence

Between the essence

And the descent

Falls the Shadow [6]

The performative space created by the artist is marked by the edges of fabric or paper or vessels, and is defined a second time by the body measure, executed by a crawling and rolling body as well as in the very act of drawing. The containers seem to be a replacement or equivalent of something between a plinth and a deprivation chamber.

There is also an act of immersion in water, liquid body ink, paper or fabric. This practice can be considered as a public ritual of purification. It is a moment when her practice gets closer to the public and it becomes in full a public appearance in those works, like Drawing the City (2004) or Leukos (2005) where the very act of outlining the body and of measuring the space by the body becomes the shared experience of numerous individuals.

The performances of Monika Weiss can be, by the notion of space, divided into two general categories - as indoor and outdoor - and by the number of actors - those she performs herself and those in which she invites the audience, especially children, to take part in them. The act of drawing seems to be strongly formative for the way Monika Weiss sees herself as a woman and artist. Using charcoal or ink, the artist draws with her eyes often closed, especially when writing the framework of a performance.

When drawing appears as a separate, smaller- scale work, the body becomes a form of density. When made as a result of performance, the drawing appears around her body, through numerous lines applied one by one by the artist's hand. It becomes dispersed, blurred, time-defined and nearly musical in the way the trace of the body is noted.

An accomplished musician, Weiss is aware of the rhythm and melody in the visual, both in works that consist of sound components and those without them. The focused and slowed-down way in which she works with charcoal, ink and pencil brings different results. There are drawings that seem to be sketches for the performances and there are performances that turn out to be drawings, even expanding the notion of drawing to three-dimensionality. In Weiss's work it is a profoundly extended notion of drawing. It is "Drawing as a form of choreography" [7] as described by Stephen Vitiello.

The work of Monika Weiss spans the solitary and the social: it stretches from the ritual sacrifice in performances when she acts on her own to the joyful shared experience in those she does with others, especially children. The vessel makes a form of shelter in which, no matter how much she forces her body to obey the concept, she protects herself from the external world. The body is here both captured and protected.

Weiss opens up a field for considering passivity and vulnerability as a form of safety. Isolation and entrapment provide the feeling of security, the most desired and cherished inclusion. Weiss is extremely smooth when dealing with the space of her own intimate experience, rituality and transgression from that of the viewer. From here, there flow suggestions of clandestine unspoken desires and she invites the viewer to a shared field:

Between the conception

And the creation

Between the emotion

And the response

Falls the Shadow [8]

And that is a shadow of her own.

Aneta Szyłak, Gdańsk, 2005

Notes:

[1] Monika Weiss: Between Presence and Perfomative Memory, video presentation and conversation with curator Aneta Szylak, Wyspa Institute of Art, Gdańsk, March 23, 2005

[2] Artist Talk moderated by Nathalie Angles, Chelsea Art Museum, New York, In conjunction with solo exhibition Monika Weiss: Vessels, March 20 - April 17, 2004

[3] Gedankenart ist ein Kunst. Ewa Partum Retrospektive 1965-2001, ed. Angelika Stepken, Badischer Kunstverein, Karlsruhe, 2001, p.11

[4] Piotr Piotrowski, Znaczenia modernizmu. W stronę historii sztuki polskiej po 1945 roku, Poznań, 1999, p.111

[5] In her later practice, Abakanowicz started to work with more general, existential issues rather than the specifics of feminine experience. See the remarks of Piotr Piotrowski in Znaczenia modernizmu, pp. 111-113

[6] The works can be seen in a text by Dorota Monkiewicz A Panoramic View: Art by Women, Feminine and Feminist Art in Poland after 1945 published in: Architectures of Gender: Contemporary Women's Art in Poland, ed. Aneta Szyłak, Warsaw/New York, 2003, p. 27

[7] Stephen Vitiello "Drawing with Body, Drawing with Sound" in Monika Weiss: Vessels, Chelsea Art Museum. 2004

[8] T. S. Eliot, The Hollow Men, 1925

Aneta Szyłak

Curator and art theorist, founder and artistic director of Fundacja Alternativa, co-founder and director of Wyspa Institute of Art 2004-2014), and Vice-President of the Wyspa Progress Foundation. In 1998, Aneta Szyłak founded with Grzegorz Klaman the Łaznia (Bathhouse) Centre for Contemporary Art and was its Director until spring 2001. Her exhibitions are characterised by a strong response towards the cultural, political, social, architectural and institutional specificity and include in 2009 „Over and Over Again 1989-2009“ at Wroclaw Centennial Hall, 2008: „Translate: The Impossible Collection“ at Wyspa, „Chosen“ in Digital Art Lab in Holon (Israel) in collaboration with Gali Eilat in 2006: Ewa Partum: The Legality of Space at Wyspa and a group show You won’t feel a thing: On Panic, Obsession, Rituality and Anaesthesia in Kunsthaus Dresden. which included the work of Monika Weiss, and Artur Żmijewski: Selected Works at Wyspa. Dockwatchers [2005, Wyspa], Palimpsest Museum [2004, I Lodz Biennale], Health & Safety [2004, Wyspa], Architectures of Gender [2003, SculptureCenter, New York], All You Need is Love [2000, CCA Łaznia]. Her writings have been published in Aprior Magazine, n.paradoxa, Art Journal, ArtKrush. Art Margins. In 2005, she was given the Jerzy Stajuda Award “for independent and uncompromising curatorial practice”.