Mark Mcdonald

Drawing Consciousness: Monika Weiss

by Mark McDonald

in Monika Weiss-Nirbhaya, Centre of Polish Sculpture in Orońsko, 2021, pp. 54 - 76

Some explanation is needed to account for what could be regarded as the deliberately conservative tactic of isolating drawing, one element of Monika Weiss’ transdisciplinary practice in which performance, sound, video, photography, drawing, and objects, together create experimental spaces, sentient states and generate non-linear narratives. [1] Drawing cannot be separated from its codependent allies, but Weiss has repeatedly made the point that drawing is at the heart of her practice, thereby recognizing its distinctiveness.

For Weiss, drawing embodies and expresses the passage of time, repetition, suggestion, and repercussion; while also celebrating the facture of media (the possibilities that physical materials allow). In this way, the artist’s practice has its basis in traditional methods, where drawing ‘gives credibility to all other media imposed.’ [2] Unlike other elements of her work — digital images, words, music and sound — drawing, through asserting its authority, implies permanence, but this too can dissipate and become a vestige where the mark becomes a trace. [3] Weiss’ drawing oscillates between proposal and presence, the allusive and the tangible where it competes (not in a precocious way) to establish its unassailable position in the consciousness mediated by the artist. [4]

How does drawing calibrate to its purpose? A first step toward forming a coherent response is to recognize that drawing serves different purposes within Weiss’ practice; thereby demonstrating her belief in its efficacy. At one end of the spectrum, modest preparatory drawings explore initial ideas from which greater ambition unfolds. Function articulates purpose, allowing the work to exist having achieved the task it was meant to fulfill. For example, a drawing for Weiss’ current project Nirbhaya, like an architect’s rendering, provides basic measurements and a scale for the proposed structure [fig. 4].

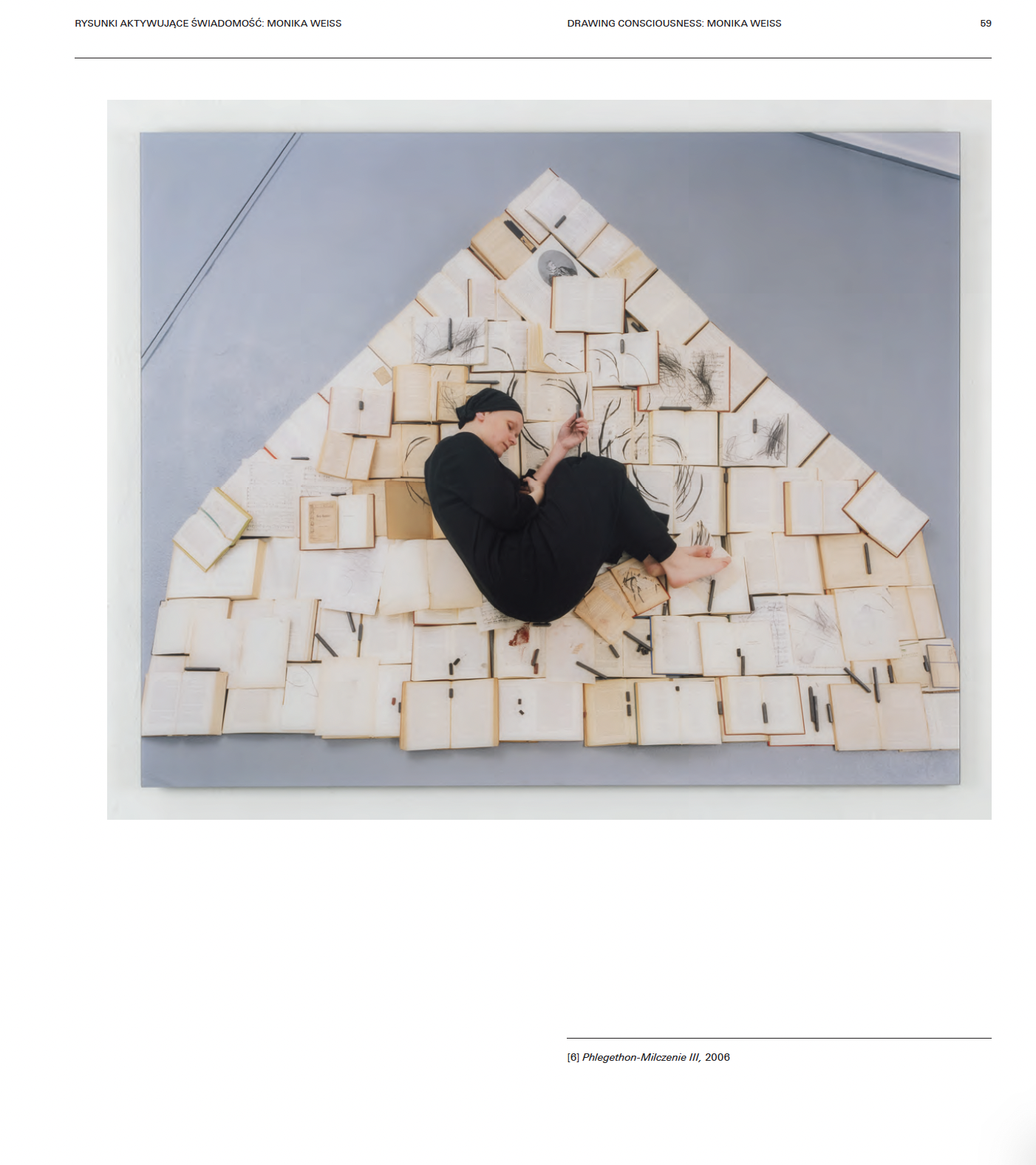

Other drawings isolate specific motifs in order to explore and map ideas contained within this project. Nirbhaya III takes the female figure that is central to the construction and views it from behind [fig. 2]. This form is a leitmotif in Weiss’ visual language where it embodies the artist’s principal concerns relating to the body as a site of profound temporal and metaphysical expression. Other drawings are more ambitious, such as Kordyan II [2005 fig. 3]. Inspired by Hans Holbein the Younger’s painting, the Body of the Dead Christ in the Tomb (1521), Kordyan II is a large pencil and charcoal composition on rice paper depicting a prostrate body. [5] The drawing includes two pages from the 1833 drama, Kordyan, by the Polish Romantic poet Juliusz Słowacki. The page on the left contains references to being a refugee (as Słowacki himself was), diaspora and an allusion to a mother and son relationship based on separation. The page on the right refers to the historical hero Arnold Winkelried who sacrificed himself in battle for the benefit of his country. The work responds both to internal visual relationships and external associations. It has been widely exhibited, including the Five Rivers survey of Weiss’ work at Lehman College Art Gallery, New York, in 2005; along with other large, independent drawings, the majority of which focus on the body and its expressive agency.

Some of Weiss’ most compelling drawings are performative wherein performance emerges from the experience of drawing itself. Mark making is entwined with the encompassing of physical movement so as to communicate conditions associated with the artist’s presence in a public space: and lament and trauma, themes that run throughout her work. [6] In these works, drawing transcends its putative or more recognizable function, and conveys heightened performative awareness forged through the unassailable connection between body and the marks that it is capable of producing [see figs 9 & 12]. Here, boundaries become blurred, revealing both the richness of the artist’s practice and the peril of imposing categories. Performativity can also be found in individual works, for example Dwie [fig. 5], one of a group in which Weiss used her arm to smear charcoal, evoking movement, and creating a ghostly outline of her body curled and standing. [7]

The above summary introduces the types of drawing Weiss engages in to reveal their range. Empirical considerations aside, embodied contents emerge. Weiss’ drawings are connected by sensation’s capacity to feel or experience subjectively — sentience — they act as agents for the feelings and states they convey. Drawing also acts as interlocutor where, distinct from the artist’s presumed intention, the mark making addresses its own subjectivity. These qualities convey the modalities of Weiss’ practice, and in particular drawing as performance. Guy Brett writes eloquently of the ‘stage’ in Weiss’ work where ‘action is minimal and everything works toward the intensification of the human presence.’ [8]

In one of the artist’s earliest performances, Drawing Room (Achea Rheon: River of Sorrow) at the Whitney Museum of Contemporary Art in 2003, the gallery floor was covered with white photographic paper upon which the artist lay holding sticks of black charcoal in both hands drawing around her body. The use of two hands is significant for it relates to another of the artist’s principal concerns, music, and in particular the action involved in playing the piano. Two hands divide the act of drawing, denying the traditional one-handed method that determines the relationship between the artist, the surface and the subject. Other sticks were scattered on the paper, issuing an invitation for children to participate. Some imitated the artist, others struck out on their own path [fig. 9]. A video camera positioned above the participants projected footage onto the wall, thereby collapsing the actions with their presentation. The aerial view is present throughout Weiss’ work, where the separation of space effects a form of disembodiment (ascending and descending), as if the viewer is witnessing actions at a remove, when they are immediately before them.[9] Drawing Room was organic. Multi-layered repeated lines defined the participant’s physical experience, capturing responses to an ostensibly shared act that was described by the artist as the ‘quietly floating waters of a river’ (Achea Rheon). [10]

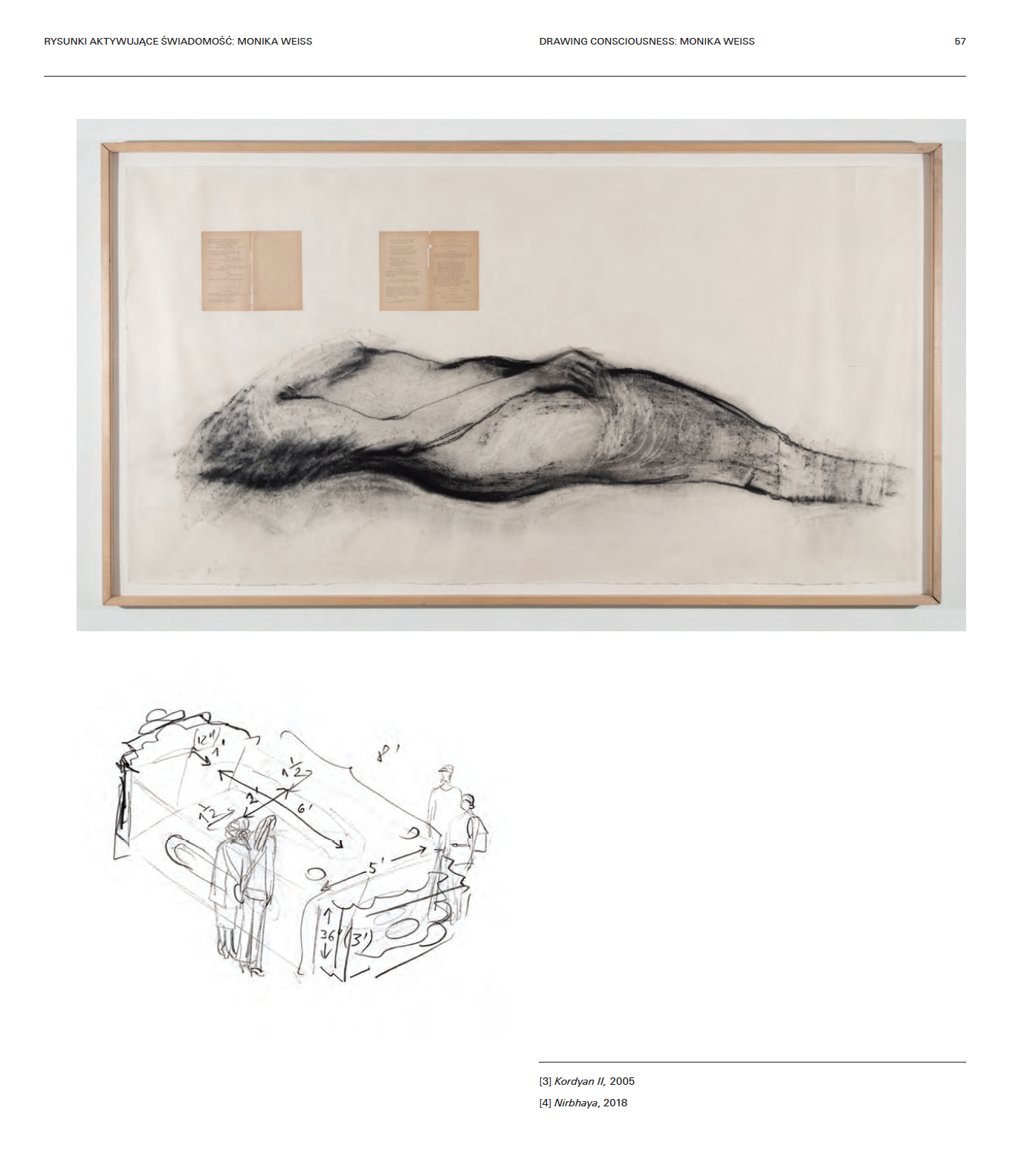

Weiss’ performative drawing is not always collaborative in the sense described above, but her solitary actions are carried out both with and without an audience, thereby establishing a tension between action and observation. As part of the installation Phlegethon-Milczenie at Inter-Galerie, Potsdam (2005, and other locations since) the artist, with eyes closed, lay upon a bed of open books by German authors who had been revered or rejected by the Nazis. [11] As she crawled and moved in this dormant yet active state, Weiss drew on the pages with charcoal, imposing her mark on the printed typography [fig. 6]. From Greek mythology, Phlegethon (the river of fire) was one of the five rivers of the underworld. ‘Milczenie’, whereas, in Polish means silence, or the inability to speak. By virtue of Weiss’ choice not to see — thereby denying her the opportunity to choose or to plot a course of drawing — the generation of marks undermines the authority of the printed texts, where invasive non-lexical lines form a network of visual signs, in order to obscure the words that silently resist effacement. The act is not accidental for it addresses the artist’s desire to articulate presence though restraint.

Guy Brett describes Weiss’ artistic restraint as an economy of means through which she achieves a greater power of expression. [12] There are no dramatic gestures, the artist does not explain her actions, and the dilated embodiment of graphic movement is closer to enactment than performance. [13] A comparison can be made with music, where sensation requires neither explanation nor embellishment. Phlegethon-Milczenie included music composed by the artist incorporating fragments of pieces by Joseph Haydn and Giovanni Battista Pergolesi, and imagery of the burning book. Weiss explains how she explores ‘[…] the important relationship between drawing and sound/music, focusing on the time-based and rhythmic qualities of drawing and the spatial and sculptural properties of music/sound. Both relate to the language the body.’[14] And so, the rhythm activated by the elements combined reveals a dedication to each, recognizing their distinctive qualities and harmonious equanimity. This is the substance of Weiss’ performance where the substantial blends with the ephemeral, marks of physical acts, aural and visual prompts, feeding the reserve of memory.

A characteristic of performance is its transitory nature, giving rise to questions of what remains. To what extent can drawing embody that to which it pertains? The ephemeral installation Leukos-Early Morning Light took place over three days in September 2005 at Lehman College and, in the following year, shown as an exhibition at the short-lived Remy Toledo Gallery in New York (a spaced dedicated to showing the work of feminist artists). At Lehman, drawings were created by the artist and other participants by tracing the outline of their bodies on large sheets of cotton to produce a syncopated rhythm of silhouettes that were then altered through wind and rain. What began as indelible marks with a specific temporal and spatial relation to the body became blurred and indistinct (a trace) mirroring the ephemerality of the installation and capturing the quality of dissipation mentioned earlier.

Between Drawing Room, Phlegethon-Milczenie and Leukos there is a shift in the agency of drawing that has to do with articulating marks. Drawing is either a solitary act where the audience is presumed, but not necessarily seen, or drawing is communal and collaborative. In both, there is an element of timelessness, where drawing is part of a reversible trajectory determined by the body as entity and presence, not the motivating hand alone. At this point seeing and non-seeing is less important because memory is the place where the graphic resides. As the following discussion demonstrates, so much of Weiss’ work evokes historical memory — what has happened, how it is remembered — its relevance now. Drawing empathetically unites and combines.

One of Weiss’ most ambitious and compelling public art projects was Drawing Lethe (Lethe: the river of oblivion) organized by The Drawing Centre in New York in 2006 [fig. 12]. It was performed across from Ground Zero in the World Financial Center Winter Garden at a time when the work to recover bodies was still underway. Over the course of four days, Weiss crawled slowly in silence across an enormous white muslin canvas punctuated by evenly spaced palm trees drawing around her body with charcoal, leaving traces of her movement and records of her presence. People joined the event, principally a group of women, but other adults and children as well, producing similar outlines. Graphic catharsis conveyed through the multitude of marks demonstrated the validity of participation from the core to the periphery of experience. The fabric became a shroud devoted to those killed by the attacks on September 11, 2001, validating their absence, enabling their memory. A key element of the project was sound — composed by the artist with the participation of the countertenor Anthony Roth Costanzo — that was emitted through speakers positioned beneath the ground. The unfolding enabled by sound and drawing was described by the artist as ‘a site of trauma [that] became a landscape of drawing and sound.’ [15] The project elegantly communicates Weiss’ conception of drawing, that Stephen Vitello describes as ‘a form of choreography. ’[16] The choreography is measured and restrained, where the artist has complete confidence in the media and the graphic to adequately accomplish its purpose.

Drawing Lethe and other works that enact drawing, embody endurance and the concentration on physicality. Lying down is also a widespread act of political resistance and the drawn marks expressive of that prone and vulnerable state. Julia Herzberg describes how Weiss ‘[…] works with her prostrate body as symbolically against and opposing the notion of the heroic body, one historically in an upright position, often representative of power.’ [17] Weiss has described the significance of lying down as an ‘ethical stance’ a symbolic form of letting go. [18]

Sustenazo was an exhibition that originated in 2010 at the Centre for Contemporary Art, Ujazdowski Castle, Warsaw, and shown two years later at the Museo de la Memoria y los Derechos Humanos, Santiago de Chile.[19] Sustenazo explored the experience of Lament (Sustenazo in Greek renders as sigh, lament together audibly) through relating it to the expulsion by the German army of patients and personnel from the Ujazdowski Hospital during the Warsaw Uprising in 1944. The exhibition combined books, drawing, photography, sound, and video to simultaneously express condemnation and grief at the brutality of what had taken place; acts of resistance to forgetting, which is central to the Museum’s mission. [20] Drawing was integral to its conception and was deployed by Weiss in different ways. The artist’s gloved hand is shown smearing charcoal over a 1942 German map of eastern Europe, one that transforms into a medical photograph of a woman’s breast, like a surgeon preparing a patient, but here with the intention of concealing or disfiguring something that should not be seen or remembered, a form of retrograde amnesia (https://streamingmuseum.org/monika-weiss/).

The action and the media veils and obscures historical time, suggesting grief through staining. Continuing Weiss’ earlier practice of incorporating texts, the exhibition contained medical books and others by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe that Weiss drew on, interrupting their contents and meaning [fig. 7].[21] Many of the drawn anthropomorphic forms echo the artist’s prone body, curled up, protective yet productive, evoking the presumed condition and fetal position of patients who had been brutally expelled. Writ large, similar forms in charcoal, graphite powder and pencil were drawn on rice paper that had been placed on top of narrow WW2 stretchers for transporting patients. The figures as palimpsest come to the fore as disembodied phantoms either facing the viewer (insisting on the present) or turned away (looking to the past) [fig. 13]. Through acknowledging the perversion of expelling people from the hospital — a site defined by its primary function of care — historical memory was powerfully restored to the present through these interconnected sequences of marks, texts, images, and sounds.

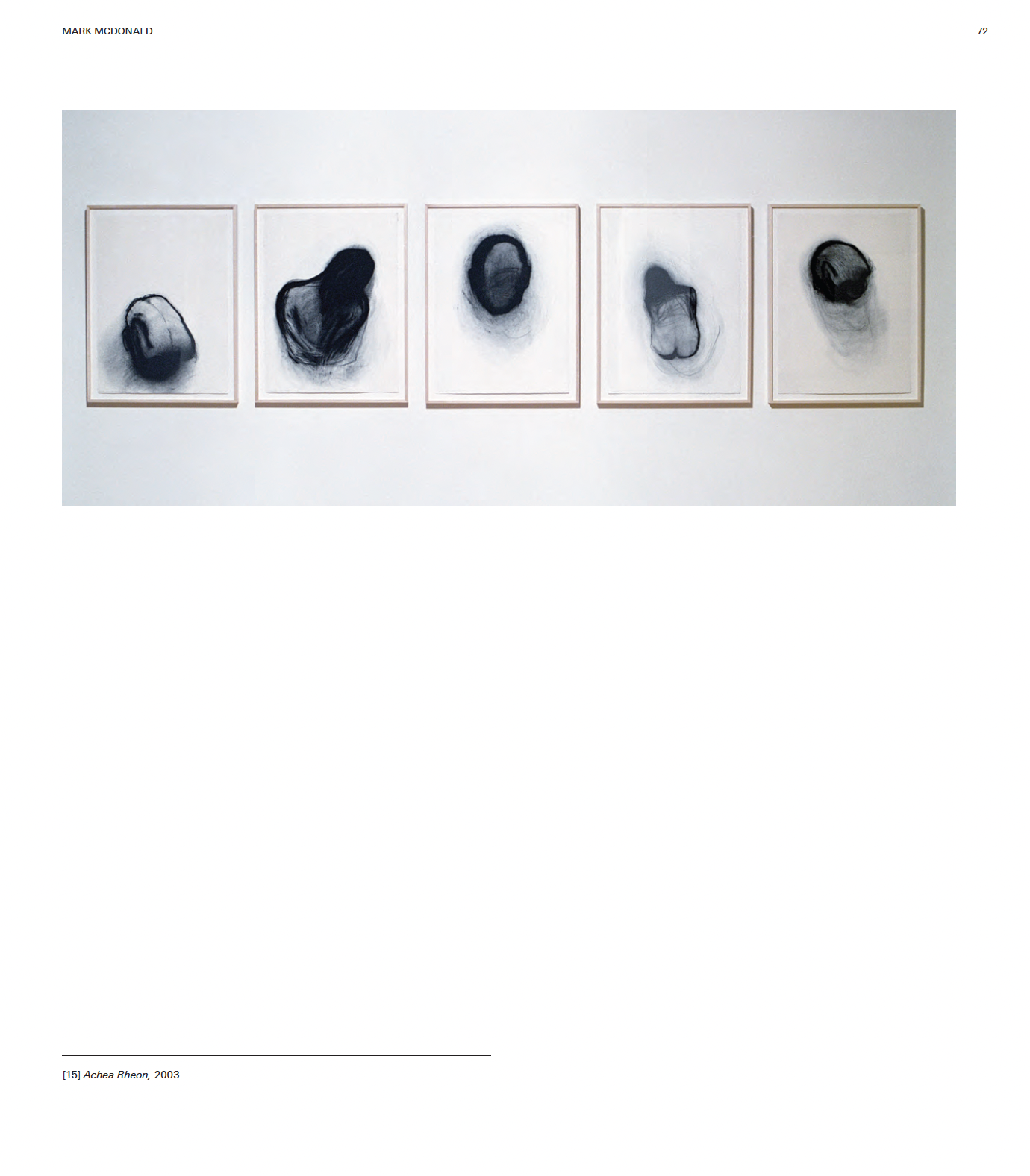

Drawing and performance are expressed differently throughout Weiss’ work. In the examples discussed above, the combination and resolution of elements (drawing, music, video, objects) depends on the articulation of each while acknowledging their codependence. Elsewhere, elements are realigned where drawing, rather than its association with performance or enactment is the focus, through prioritizing surface and media. The five large charcoal drawings Achea Rheon (Rivers of Sorrow), 2003 [fig. 15] were included in the 2004 Vessels exhibition and thus, relate to a wider body of work.[22] Their shared formal qualities, however, allow them to be seen as independent works as they were intended. Four of the bodily forms appear in a state of restless flux, emerging, folding and struggling before vanishing back into the energy that initially enabled their passage. The technique reveals the artist’s dexterity and facility in which the charcoal is applied to achieve the lightest of marks to support the densely worked opaque areas. The middle drawing is counterpoint to those that flank it and embodies the moment of complete absorption where the figuration hovers between dissolution and emergence, before setting off on a path that is more recognizable. Framed and evenly spaced on the wall, this group demonstrates the artist’s trust in the efficacy of the medium to propel what motivates the works: the articulation of movement and trans- formation, the antithesis of stasis. There are clear connections between Achea Rheon and the works described earlier where the body as conduit articulates marks. With Achea Rheon, performativity emerges at a remove, solely through drawing that is meditated and has ulterior purpose.

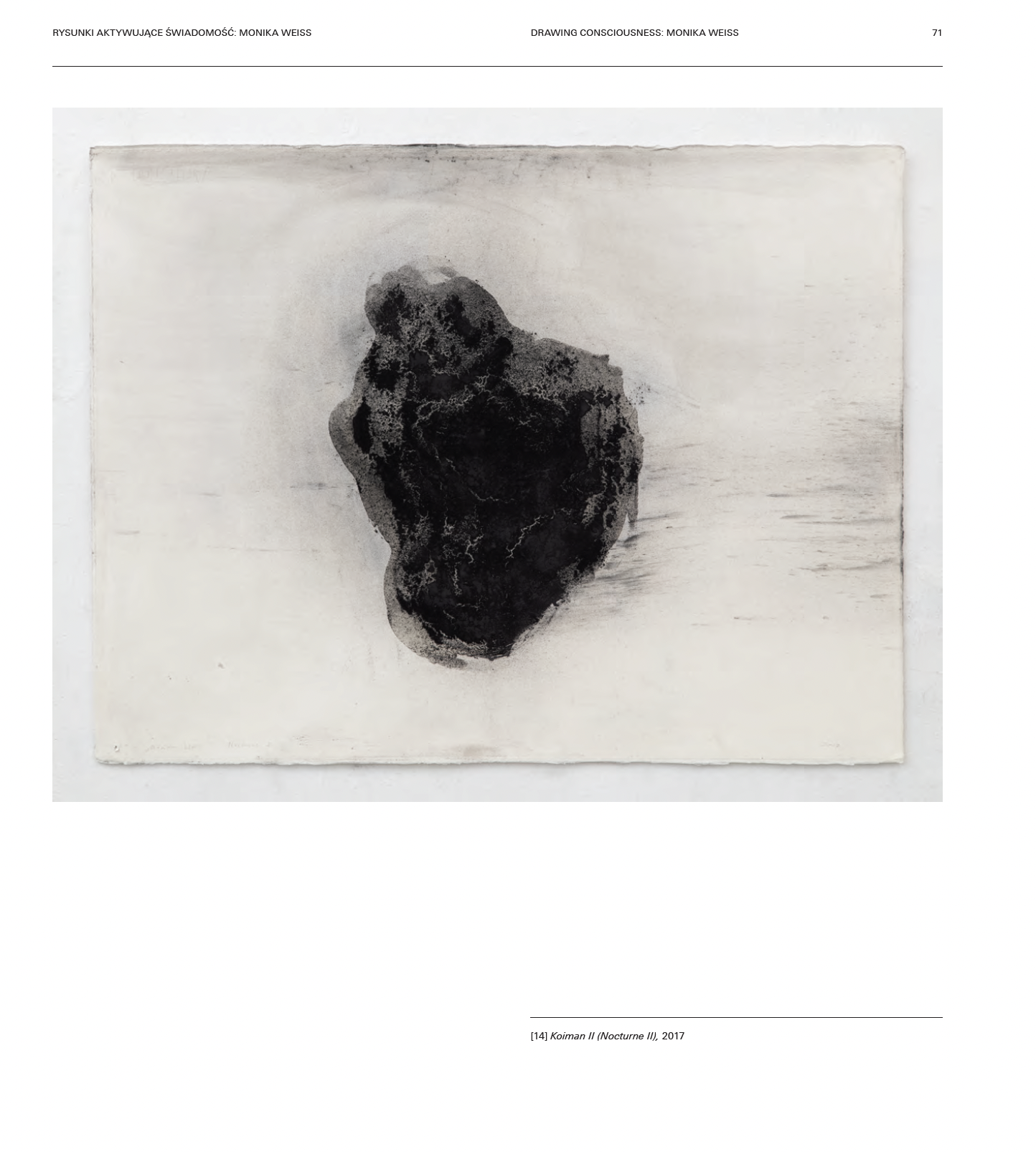

To this point, drawing and performance have been addressed with regard to the artist’s body as subject, agent and threshold: to mark, record and remember (the antithesis of erasure or amnesia). In Weiss’ recent work, her graphic index takes a different turn. Koiman II — Years Without Summers (24 Nocturnes), 2017, a deeply personal and political work, comprises twenty- four film projections, an equal number of sound compositions and large charcoal and graphite drawings. The subtitle derives from the 1815 volcanic explosion in present day Indonesia that affected the global environment leading to what was described as “a year without summer” (in 1816). The ensuing darkness in parts of the world caused by volcanic ash was described by those who witnessed it and is compared by Weiss to the darkness that envelops our world: refugee crises, climate change and the rise of blinkered nationalist ideologies. In the film, set against desolate and dark landscapes and sites of abandonment, the protagonist gestures and moves silently. The drawings that evoke the explosion appear momentarily superimposed on the figure creating a suggestive union [figs. 10 & 14]. Whereas the drawings were conceived as independent works, their relation to the film enriches their autonomy. Graphically they resist, their media (graphite powder and archival glue) links directly to the historic past while evoking the notion that through the obscurity of ash, our culture cannot perceive its own future.

In addition to recognizing the qualities of charcoal that adapts to the artist’s needs (its capacity to be held firmly, crushed, its ability to stain, and the symbolic associations), Weiss uses other materials with comparable purpose. Graphite powder for example, when mixed with water has properties similar to ink. The type of paper is also carefully considered. Since about 2005, Weiss has often worked on Japanese rice paper because of its transparency and ability to evoke the surface of skin, allowing her to double the metaphorical connotations when so much of her work revolves around the body. Equally striking is Weiss’ use of latex combined with charcoal establishing contrasts between smooth and rough, transparency and opacity, that transmits vulnerability and strength [fig. 8]. Weiss describes the process: ‘I use latex that weather balloons are produced from, … it comes in sheets, that look and feel like skin, my skin I guess. I try to draw through it, both latex and rice paper are fragile and hard to draw on, they also retain all traces, there is no way to erase anything.’ [23] Weiss’ search for techniques that adequately express artistic preoccupations is a hallmark of her approach, wherein the media is interrogated for its capacity to perform the mark and leave a trace, a path that multiplies and incessantly divides.

To end with Nirbhaya, where the graphic ascends a different, though no less persistent path. The violent foundations for this piece are discussed elsewhere in this catalogue, but to reinforce its conceit, Nirbhaya is an anti-monument, a sculpture, a sarcophagus, and set of video projections that show a young woman moving slowly as if lying or dancing in the sarcophagus, a process of gradual transformation expressing lament, silence, and the locus of trauma. Nirbhaya embodies stability, transience, and decay, all of which can be traced through the artist’s drawings for this project [figs 2 & 4]. Weiss has worked with water since the 1990s where it is symbolically associated with submersion, initiation, rebirth, and cleansing, conveying the idea that fluidity does not respect boundaries. [24]

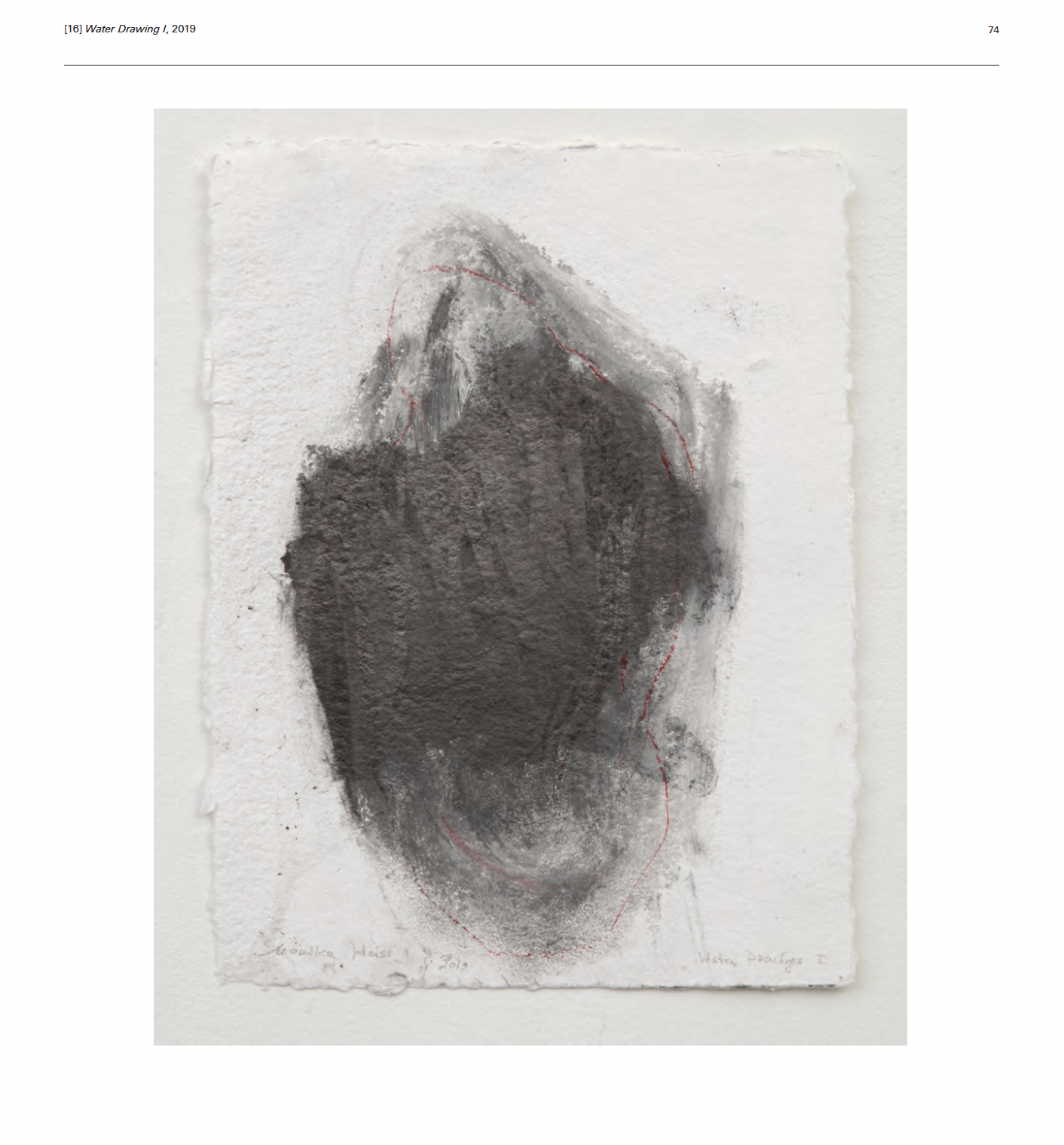

The relationship between water and drawing has a long and distinguished history: when combined with other media it allows for specific fluid, transparent and even accidental effects. Weiss’ use of an aqueous medium recalls her Milk Series (2001), a group of small drawings created through combining pencil, crayon, hair-dye and milk on aged paper. [25] For Nirbhaya a large group of drawings (cantos) explore the connections between the sarcophagus, the suggested presence of the woman, and how forms merge and become distinct through their aqueous load, presumed to be transparent yet inherently obscuring [fig. 16]. These recent drawings are a salient reminder of Weiss’ ongoing practice as an artist, and her commitment to exploring new methods to embody conditions and states that perpetually outline the world providing it with her own contours.

Mark McDonald, New York, 2021

Notes:

[1] For an overview of Monika Weiss’ practice, see Julia P. Herzberg, “Monika Weiss’ Language of Lament: History and the Body”, in RECALL, BWA Zielona Góra, 2012, pp. 97–99; as well as Guy Brett, “Monika Weiss: Time Being”, in The Crossing of Innumerable Paths. Essays on Art, 2019, Ridinghouse, pp. 85–92 (originally published in Monika Weiss: Five Rivers, 2005).

[2] Aneta Szyłak, “Your trap shall be your shelter: the hidden desires and public appearances of Monika Weiss”, in Susan Hoeltzel (ed), Monika Weiss: Five Rivers, New York: Lehman College Art Gallery, 2005, pp. 49–60.

[3] In a conversation between Nathalie Angles and Monika Weiss (April 8, 2004 Chelsea Art Museum, New York), Angles asked: ‘You talk about “mark” and I would describe your performative installations as “mark making” rather than “trace making”. There is a very fine distinction between the two... “Mark” is defined as “a visible indication made on a surface” whereas “Trace” is a “visible mark left by the passage of a person or animal or vehicle”. To which MW responded ‘I am interested in the history of mark making in art as a history of revolt against the “eternal darkness” (as Dostoyevsky’s protagonist in The Idiot Myshkin said, as he stood in front of Hans Holbein’s “Dead Christ” painting). Mark making is about gesture. It appears to be hopeless and insignificant; and yet it provides an evidence of existence, its “trace”’.

[4] For a discussion of Polish and other women artists for whom performance is central to their practice, see Aneta Szyłak, “Your trap shall be your shelter: the hidden desires and public appearances of Monika Weiss”, in Susan Hoeltzel (ed), Monika Weiss: Five Rivers, New York: Lehman College Art Gallery, 2005, pp. 49–60.

[5] Kunstmuseum, Basel. Oil on panel.

[6] James D. Campbell, “Drawing on Syncope: The Performativity of Rapture in the Art of Monika Weiss”, in Susan Hoeltzel (ed), Monika Weiss: Five Rivers, New York: Lehman College Art Gallery, 2005, pp. 33–47.

[7] Pennina Barnet, “Performing the Drawing” in Monika Weiss: Vessels, New York: Chelsea Art Museum, 2004, p. 3.

[8] Guy Brett, “Monika Weiss: Time Being”, in The Crossing of Innumerable Paths. Essays on Art, 2019, Ridinghouse, pp. 85–92 (originally published in Monika Weiss: Five Rivers, 2005).

[9] Weiss has continued to adopt a similar practice for later projects. For Horos I (2007 Real Art Ways, Hartford, CT) and Horos II (2008 Contemporary Art Center in Opole, Poland) a camera was installed on the room to record the actions of drawing on fabric below. For a different purpose in 2012, Weiss recorded footage from a plane to reveal a site of desolation that was a small German concentration camp for Jewish women, Gruenberg, now located in Zielona Góra. See Wojciech Kozłowski, “It is with the wreckage and rags that one should intend to write History” in Recall, BWA Zielona Góra, 2012, p. 92-94.

[10] Monika Weiss, “Drawing Room (Achea Rheon)”, in Monika Weiss: Vessels, New York: Chelsea Art Museum, 2004. p. 28.

[11] In 2006 Phlegethon-Milczenie was shown at Kunsnhaus Dresden. It became part of the collection of the Cisneros Fontanals Art Foundation in Miami, where it was shown as part of Miami Basel in 2006 and 2008. Most recently (February 2018) it was commissioned as an outdoor ephemeral public project by the city of Dresden to commemorate its liberation/ destruction in 1945.

[12] Guy Brett, “Monika Weiss: Time Being”, in The Crossing of Innumerable Paths. Essays on Art, 2019, Ridinghouse, pp. 85–92 (originally published in Monika Weiss: Five Rivers, 2005).

[13] On this distinction, see James D. Campbell, “Drawing on Syncope: The Performativity of Rapture in the Art of Monika Weiss”, in Susan Hoeltzel (ed), Monika Weiss: Five Rivers, New York: Lehman College Art Gallery, 2005, pp. 33–47.

[14] The artist cited by Julia P. Herzberg, “Monika Weiss’ Language of Lament: History and the Body”, in RECALL, Zielona Góra, 2012, pp. 97–99.

[15] Monika Weiss, „Nirbhaya. Triumphal gate lying down — memory, amnesia, flatness, wrath. Notes towards a project”, in Eulalia Domanowska and Marta Smolińska (eds), Sculpture Today 4: Anti-Monument: Non-Traditional Forms of Commemoration, Orońsko: Centre of Polish Sculpture in Orońsko Press, 2020, pp. 191–199.

[16] Stephen Vitello, “Drawing with Body, Drawing with Sound” in Monika Weiss: Vessels, New York: Chelsea Art Museum, 2004, p. 29.

[17] Julia P. Herzberg, “Monika Weiss’ Language of Lament: History and the Body”, in RECALL, BWA Zielona Góra, 2012, pp. 97–99.

[18] Guy Brett, “Monika Weiss: Time Being’, in The Crossing of Innumerable Paths. Essays on Art, 2019, Ridinghouse, pp. 85–92 (originally published in Monika Weiss: Five Rivers, 2005).

[19] See the interview and essays in Julia P. Herzberg (ed), Monika Weiss: Sustenazo (Lament II), Santiago de Chile: Museo de la Memoria y los Derechos Humanos, 2012. See also the related project, Shrouds (2012) in RECALL, BWA Zielona Góra, 2012.

[20] On this point, Julia P. Herzberg, “Monika Weiss’ Language of Lament: History and the Body”, in RECALL, Zielona Góra, 2012, pp. 97–99.

[21] Weiss had earlier used Goethe’s books in a site-specific installation in Berlin, part of the exhibition Wa[h]re Kunst (2009). The artist lay on a bed of books, spitting black fluid from her mouth, a practice linked with drawing insofar that it stained the texts that both produced.

[22] Vessels. Chelsea Art Museum, New York, 2004.

[23] Email to the author, May 28, 2020.

[24] See for example, Ennoia (2002, 2004) and Elytron (2003). Also, transcript of conversation (Baptism of Water) between William Anastasi and Monika Weiss in Monika Weiss: Vessels, New York: Chelsea Art Museum, 2004, pp. 14–19.

[25] See James D. Campbell, “Drawing on Syncope: The Performativity of Rapture in the Art of Monika Weiss”, in Susan Hoeltzel (ed), Monika Weiss: Five Rivers, New York: Lehman College Art Gallery, 2005, pp. 33–47.

Dr. Mark McDonald

Dr. Mark McDonald is curator at The Metropolitan Museum of Art where he is responsible for Italian, Spanish, Mexican and early French prints and illustrated books. He joined The Met in 2014 after working at the British Museum as curator. He has curated exhibitions at the British Museum and Museo Nacional del Prado among others. He has published widely on the graphic Arts. The Print Collection of Ferdinand Columbus: 1488-1539 (2006) won the Mitchell Prize for Art History and Apollo Book of the Year. More recent publications include Renaissance to Goya: Prints and Drawings from Spain (2012), a study of Goya’s Disasters of War (2014), six volumes on the Print collection of Cassiano dal Pozzo (2019) and Alonso Berruguete: First Sculptor of Renaissance Spain (2020) that was recently awarded the Eleanor Tufts Prize. He has taught at the Courtauld Institute in London and IFA in New York.