Vanessa Gravenor

Monika Weiss’ Two Laments

by Vanessa Gravenor

published in n.paradoxa: international feminist art journal, volume 37, January 2016 (SOUND?NOISE!VOICE!), KT press, London, pp. 83-88

What is a victim and what does a victim resemble: the innocent, the weak, the lost or departed? An often cliched, empty word, full of binary oppositions and pitfalls, the state of victimhood is also a limit, a becoming, a production. Feminist critiques have long opposed the position of victimhood that, categorically speaking, is often an empty terrain, a homogenous site, where characters are voided and subjects lose their agency. This is of course, why artists and thinkers should resist this terminology. However, if a more nuanced understanding is permitted, because a victim is a production, a process where the interior is moved to the exterior, it can also be seen as a place where multiple people can form identifications with others, to move in solidarity into a "border zone" that forms in marginalization.

Monika Weiss' Two Laments, a series of video cantos that address the event of rape in India, specifically the recent rape of Jyoti Singh that was widely reported and showcased with almost a spectacular quality in the media, questions both how one can be emancipated from the residual pain of victimhood, but also how victimhood, especially transformed by the phantom language of memory, can be a site for co-shared resistance. Initially paradoxical and self-contradictory, Weiss asks questions that many feminists or artists would often deem taboo. Her piece thus forms a thorough meditation upon trauma and pain, so that others, namely women who have also suffered bodily crimes, can come together in a type of crowding. Weiss is interested, not in the personal dissemination of private pain, but the process in which the private becomes part of the public domain. In remembering these crimes through the form of video, Weiss’ Two Laments brings further visibility to rape crimes, while redefining the activity of mourning as an activity where many people can share in a process of community making.

Beginning with a singular event, the 2012 gang rape of Jyoti Singh, also called 'Nirbhaya' or 'India's daughter', the first video canto circles around the traumatic gang rape of the 23-year-old women who was returning home with her boyfriend after seeing a movie. The activity of rape was a gesture by the men, one could say, against the mobility of the female. The rape was also contextualized as part of a series of rapes happening in India. Subsequently, the rape of Jyoti Singh sent waves of protest across India, which triggered resonances around the world.

Through her recent experimental video, Weiss poses the question of how to memorialize Nirbhaya's body without further perpetrating phallocentric aesthetics often rife within mortuary culture, such as the Indian Gate a monument to the Indian soldiers who fought for Britain in the World Wars, which Weiss addresses in her final canto. Often the language of mourning is confined to a longing or desire for a lost object, a Freudian castration. This manifests itself within public aesthetics such as large vertical arches that represent the lost form. Yet, loss, for Weiss, is an experience that should create new webs, new links, so that it can be utilized as a connecting force for community building rather than something which creates permanent voids.

Within Two Laments, instead of an object signifying loss, trauma is transformed into sound. One hears this sound in the first cantos where Weiss' poem 'This is My Ribbon' appears in subtitles in the first cantos. 'This is My Ribbon' is performed in spoken word in languages of Sanskrit, Hindi, Bengali, and Oriya. These languages are meant to represent minor tongues that resist an official colonial English. It is the second canto, however, that loss is transformed into music. Weiss wrote a short melody for classical format, which an Indian Camatic Singer then performed. Here, loss is imbued with living presence and transformed into elegy. This elegy, which is performed just with the human voice and no other instruments, resists set formats and stability. The voice, a lament, often bears traces of pain and sorrow, which affects the beats and tones of the melody with a certain hysteric vibration.

Weiss's formative works addressed events during World War II and highlighted violence perpetrated against the human body, specifically the female or ill who are often the most vulnerable to casualties. These works include Shrouds (Całuny), a performance that occurred in 2012 on the grounds of a former concentration camp ruin. In the video documentation of the performance, women walk in a landscape tainted with Beckett-like sense of transcendental doom. Weiss questions how one should remember the events that have transpired when the present sites are banished to entropy or, in the case of this specific site, might be transformed into a junk space shopping mall. Moreover, an interesting relation occurs between the wandering body seen on the screens with the former Jewish workers who had left the camp on death marches.

Weiss does not address these traumatic events by traditional or didactic means. While her performance and video work can be framed under the banner of reconstructed memory, often few details about the actual historical incidents remain in her video sequences. For instance in Wrath (Shrouds IV) a digital and sound composition from 2015, a woman's body is seen transposed against the skyline of Tehran. Seen in conjunction with Shrouds II (Tahrir Square), a proposal for a performance where woman perform laments in Tahrir square to commemorate the violence perpetrated against women, this video serves as an unlikely document or encounter with traumatic memory and the present. Her work is what Griselda Pollock terms ''post-traumatic" in that it contends with events that remain within collective psychic consciousness but are unable to be fully or properly mourned because the extremity of the trauma defies speech. Such events are remembered hysterically and reappear in the present by shifting form and content. Trauma, thus, acts like a broken refrain where moments that have made a cut in the psyche replay at infinitude with no clear formal logic. One sees this here in Two Laments with the repeated text that shifts languages and transforms from transcribed text into performed singing.

Two Laments begins with foreboding silence and text over black background. Weiss has written a text that stands in for the no longer present voice of Jyoti Singh. This text consists of fragments, a text that Weiss has written herself from the point of view of Nirbhaya. The text addresses Nirbhaya's rapists and begins with the statement 'This is my ribbon, taken out of my body by you'.

Gasping is the unveiling of the unconscious, Pollock says. It is also a state before language, when words are not possible, like when in mourning. The text, which is woven in various ways throughout Two Laments, can be compared to the phenomenon of gasping, in so far as gasping is an attempt to form speech. Writing specifically on Daphne's gasp when she is threatened with rape, Griselda Pollock writes: 'Resonating within the body, the gasp is a sound of subjectivity as it registers a shocking, sudden, unexpectedly affecting encounter with something seen, felt or done to the body. '[1] Can a gasp be read into this text on the screen? Do we register it as breath or as a voice which protests against the violence perpetrated on a woman's body in these bolded white letters, capitalized as if etched within the stone of a sarcophagus? The effect of this is like a form of silent gasping in the first cantos of Two Laments.

The statement 'This is my ribbon / taken out of my body by you' connotes possession and reveals the defilement of her internal organs in this attack. In a conversation at the artist's studio in June, Weiss explained to me how this statement was taken from the public record, where one of the rapists had described Nirbhaya's intestine as a ribbon. It is through the phantom language of memory that the aggressor falsely remembers reality or that reality returns to him in estranged symbolic tones. This false remembering reveals his own lack in comprehending the shocking violence against this young woman. Weiss' use of these stark statements testify to this estranged cruelty. These phrases bear similarities to Jenny Holzer's project Lustmord where the rapists' attestations are etched into metal and represent snippets of memories while the female body is represented as under siege.

Commenting on Freud's concept of the "navel dream" where he looks inside a patient's mouth and experiences fear in the face of the abject site before him, Griselda Pollock's commentary on the limits of Freud's analysis in the face of sexual difference bear a strange resemblance to Weiss' emphasis on the block manifested in the rapists testimonies:

exploration of female corporeal intel'iority -visually peel'ing into bet· body via her opened mouth (which cannot but displace a more vaginal curiosity) - reveals a medical investigation that sublimates the infantile exotics of research into the sexual difference of the generative feminine body. This curiosity, however, meets a blockage beyond which Freud will not prnceed in his analysis [2]

This interior dream that occurs for Freud, blurs the boundaries between female figures, idols, mothers, and lovers. For Freud, Pollock concludes this visual curiosity manifests itself into a block, an impasse in sexual difference that he cannot move beyond, just like the words of the rapists who cannot move beyond the crass categorizations of Nirbhaya's body when standing before the law. They are, in a sense, also within a navel dream.

In contrast to the limits of Freud's analysis, Griselda Pollock cites Ettinger's concept of transcryptum in her book After-affects/After images: 'thus, we can conceive of a[n alternate] chain of transmission, where a subject "crypts" an object/other/m/Other, who in turn had crypted own object/other/m/Other, so that the traumatic Thing inside my mother's other is aching in me. We are now going to propose that in a similar vein the traumatic Thing of the world is aching in artworking.' In contrast to "naval dreams" 'transcryptum' is a process where the past can haunt. This haunting is not manifested within a blockage but within a movement, a mourning that leads not to the emancipation of the lost object but to a catharsis which encourages connectivity. This activity, Bracha Ettinger terms a transcryptum of memory'. [3]

A 'transcryptum of memory' is what Weiss is re-enacting within the video Two Laments, for she is asking the audience to remember and engage with a traumatic memory, not in order to be traumatized by it, but in order to openly recognize crimes which are often confined to silence. Moreover, 'transcryptum' allows for events to be linked into a web of signs, past pains or maternal aching, so that contemporary incidents, such as the rape in question that occurred on the Indian continent, does not remain isolated by time or in the private sphere of domestic life. For Weiss, this identification is extremely important, for it opens up the plane of victimhood to the zone of public collective life.

In Canto 1, the words, 'I am a martyr', flash up on the screen as provocative and quizzical words, ill fitting for the young 23 year, for they reveal fate rather than individual wish. Considering the crime of rape that made a woman into a victim rather than hero, Weiss toys with another strain of owning a label - that of martyrdom. How are we to understand Jyoti Singh as a martyr then if her rape and subsequent media coverage rendered her iconic, yet there was never a sacrificial offering of her body as often happens in mythic songs and stories? Can we even say this word "martyr" without suggesting that her rape was fated in order to warn other woman about the perils associated with independent fomale mobility within modem cities? Yet, could there be another understanding of her death in terms of ritual sacrifice: one that does not create bodily offerings but instead suggests that it exists outside of history as purely tragic?

The framing of rape as tragic is an attempt to moralize history and make it consumable, thus, forgettable. In moralizing history, we can also see history as becoming tragic and in one sense, understood only through epic. It is not only in reality, in the fetishistic words of the assailants, that we see this shift happening, where an atrocity is transferred to the sphere of drama to become comprehensible as a narrative but in the very structure of the video where the stages of this process mirror the video's separation into cantos. Weiss explained to me in an email how the Polish poet Jan Kochanowski's 'Treny' ('Laments') inspired her poem 'This is My Ribbon', which appears in the first cantos through text and sound. In 1579, Kochanowski wrote the poem to commemorate his daughter who died as a two year old child. Weiss explained to me that this was possibly the first commemorative poem not written for a King or a person in power. This was her own motivation for choosing this form for this subject.

Since Jyoti Singh is sometimes referred to as 'Nirbhaya' (meaning fearless in Hindi) and 'India's daughter', Weiss made this connection between the commemorative love of a father and the commemorative love of a nation or a nation's people. Within the cantos, it is not so much India as a nation who we see grieving over its daughter but other women and people enacting a collective pouring of emotion. This collective mourning transcends the singular event of gang rape and connects to a broader grieving of crimes perpetrated against the female form. Thus, this mourning goes beyond the historical and becomes a tragic, epic form. In epic, which has a more general, metaphorical quality, juridical guilt can be questioned and the victim can be brought to justice.

What is the connection between these collective traumas manifested through the tragic and the function of juridical guilt? A word often used [by feminist activists against violence against women!] in connection with rape crimes is "survivor" however, in the simple basic meaning of the word, the perpetrators/rapists themselves continue to live in the world - are they not also survivors? The survivors in Weiss' video are instead other women, regular citizens, who have to continue living despite the knowledge that these crimes can be perpetrated and furthermore are perpetrated to serve as warnings to other women or objects of public shame.

If we return, now, back to the words 'I am a martyr' discussed earlier, do we also see the shadow of tragedy, if we understand tragedy as a rift between responsibility and judgment that in modern times produces a lack of guilt or passage of time? These words, so oddly and uncannily resonating two meanings, defilement and sanctification, reflect the desire to turn away from shame into another form of subjective agency where a woman's death can become a symbol or icon in tragedy. Yet, even as the video certainly contains some elements of tragic iconography, such as the lamenting transcendental body of a young woman (not Nirbhaya's but that of the women protesting for her, identifying with her), there is a constant deflation and inflation that resists fixed states. This is evident in the fact that ordinary women are acting as the body of Jyoti Singh establishing a definite deflation and expansion of a martyr's body. These quotidian aspects here act as the redemption of the people who instead form and reconfigure the body of a sanctified figure, rather than offering us a woman as a singular figure acting as the redeemer.

Perhaps, we can also view these words in light of the proceeding, following, and yet-to-come cantos, some of which include different female forms performing lament. These women, choreographed by Weiss, act for and as Jyoti Singh. They use the event of mourning as a call for unification and crowding that has the potential for emancipation and change. Thus, the body of Jyoti Singh serves as another threshold for other women to become empowered and in a sense, also take in part of her body. Additionally, these women clutch a scarf that resembles a red ribbon. Held to the abdomen, this red material becomes an exterior organ also suggesting that Jyoti Singh's body has become a plane of immanence, a type of memorial.

In a text sent to the writer written by Weiss, Weiss reiterates the widely reported media statement about how the rape occurred on a moving bus. Of interest to Weiss, this bus was moving inside the interior of the city despite the fact that it harbored an act that often occurs behind closed doors. Weiss explains how she identifies Nirbhaya's body because of this site as a flâneuse, the female form of Benjamin's flâneur. The flâneuse is a female inversion of a male trope, yet, here in this case the young woman's mobility did not lead to her freedom but to her being targeted because of her public movement at will within the city. By contrast with this activity of movement and independence for which Nirbhaya was supposedly punished, her organ, the ribbon, became the symbol for her dead body in Cantos 2 and 3, where women are seen clutching a surrogate "ribbon".

On the connection of border spaces and rape, other artists have also explored this paradoxical dualism such as Amar Kanwar’s Lightning Testimonies (2007) that documented stories of rape that ensued after the partition in India in 1947. The Lightning Testimonies is an eight-channel video installation whose subject is not confined to historical cases because it also includes documentation from anti-rape protests in Manipur in 2004. This documentation brings contemporary resonances into the activity of traumatic remembrances. Separated into segments through the installation and also within the video sequence, the project explores the often-fragmented aspect of speech and memory associated with traumatic pasts. Also about the mobile female body, rape in this historical incidence was used as an instrument during partition a means to resettle lands.

These cross associations encourages country to be thought of as a porous human body and vice versa the female form can be thought of as a political entity. Like Weiss who is interested in framing the rape of Nirbhaya as a public crime on the scale of war, Kanwar also seems to be interested in the opening up of the private sphere to the public, ultimately questioning the language of History that often covers over stories that don't fit into its typical narrative. This is evident in the overlapping of tales, some that don't cohere into a narrative format, and other that feature a women speaking into the camera. The form of Kanwar's video sequences seems to begin with the incomprehensibility of the crimes, and yet, when seen in its totality, it seems Kanwar is setting up a system for the viewers to be able to take in the intensity of emotion as well as the gravity of the crimes.

Like Kanwar, Weiss is deeply committed to the reconciliation of historical, deeply imbedded memory with contemporary occurrences that signal repetitions, and horrific returns of the same. For instance in Canto 3, Weiss addresses the colonial past of the city of Delhi. Female bodies lie over former city plans that represent the city before modernization. These old fragments of a nation, now lost to time, touch on a second rape that is often eclipsed: the rape of a city by colonialism. The city, thus, acts as a second body, and second victim to a different type of violence. This city is also representative of a female body or perceived oriental or exotic zone that the West often fetishizes and thus, abjects.

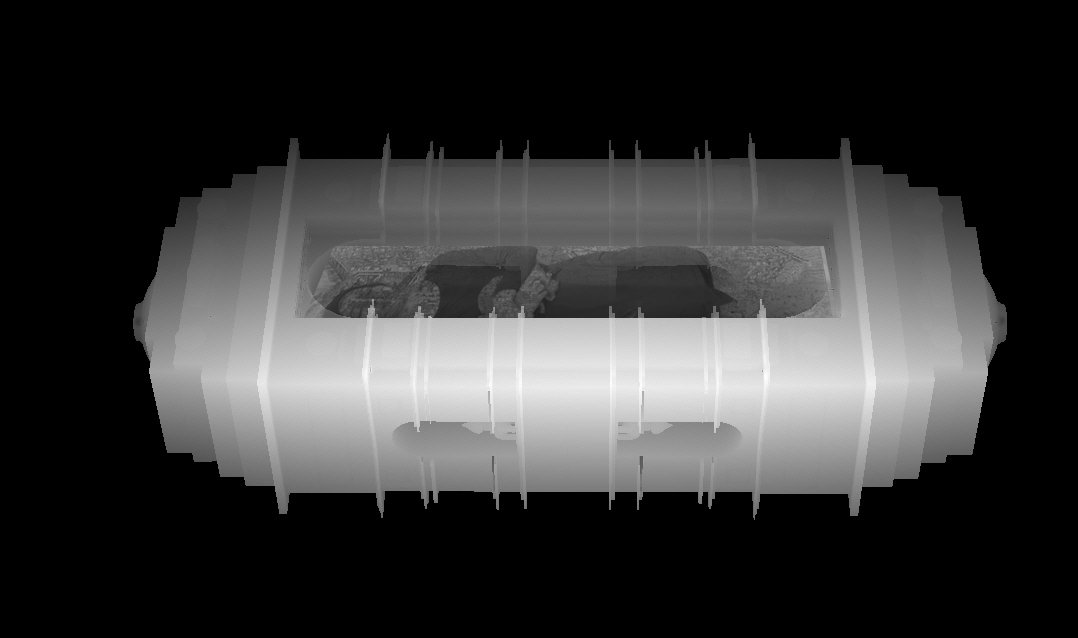

In a proposed rendering, a sketch for an imaginary performance that cannot be manifested because it would put the participants at danger, we see the India Gate, a monument to India's support in British Empire wars surrounded by female bodies. These female bodies crowd around the gate forming a horizontal mass meant to counter the vertical symbol. The gate is a monument to both India's dead soldiers, but also to the event of colonialism itself where a monarch built an Empire and used a country as both an annex and expendable labor. The gate celebrates European standards of valor in neoclassical architecture, even the commemoration revealed the systemic indentured servitude Great Britain had in place to build it. This gate is certainly an icon to the masculine, the phallic, and yet, it is also a remnant of a former time, an anachronism, that testifies to a continued state of vulnerability of a nation during times of war but also the event of rape that knows no icons, or symbols. In a rendering for a sculpture that Weiss plans to build, one sees the Indian Gate on the ground doubled as if it was in mirrored perspective. Lying vertical, the gate is rendered unusable, non-utilitarian.

The logic of this horizontal, doubled gate shares a similar logic with Robert Gober's sculptures that rendered utilitarian objects, such a faucets, and bathtubs, unusable. Gober's sculptures emphasize the queer, diseased body that becomes impotent. Like Gober's sculptures, Weiss associates this memorial object with the raped body, generally speaking, that has also been defiled internally. Weiss intends to fill the internal crevice, the arched gate (once mirrored forms a basin shape) with the projection of a body.

Weiss' work maps the body of Jyoti Singh. It is chartered, drawn, and cut by another knowledge system, that of patriarchy. In Edward Said's seminal text Orientalism, he explains how the West has a tendency to survey and charter what they deemed the developing world: 'It is natural for men in power to survey from time to time the world with which they must deal'. The West, he explains citing Kissinger, was a world full of external knowledge, affected by the Newtonian age. The East, however, was an internal system that never experienced empirical knowledge. Thus, a Western vision externalizes subjects whom once experienced interiority and turns a nation, so to speak, inside out: twisting routes transform into grid and archaeologists suddenly discover groups of study. [4]

Although Said is only deconstructing the damage colonialism did in its view of the East and moreover the residual affects this thinking has on modem thought, one can see many similarities between this critiques and that of a feminist agenda that also deconstructs the residual affects of the male gaze. In Weiss' video, these two critiques go hand in hand. The demolition of the female form is akin with the destruction and framing of the east by the likes of Kissinger. By interweaving these two critical narratives, that of feminism and that of colonialism, Weiss is claiming that the violence perpetrated to women in sex crimes carries the same gravitas as the public violence in the city, and thus, should have the same visibility, the same critical language, and the same public reminders.

Vanessa Gravenor, Berlin, 2016

Notes:

Monika Weiss’ Two Laments was recently on view as a solo exhibition curated by Amit Mukhopadhyay at Sanskriti Museums, New Delhi, India (April, 2015) and part of group presentation at Forum 5, Bolognano, Italy (June, 2015): http://polishinstitute.in/two-laments-by-polish-artist-monika-weiss-the-artist-residency-at-the-sanskriti-kendra-15-march-2-april-2015-new-delhi/

[1] Griselda Pollock, After-affects/ After-images: Trauma and aesthetic transformation in the virtual feminist Museum (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2013) p. 47

[2] Ibid pp. 57-58

[3] Ibid pp. 24-25

[4] Edward Said, Orientalism (London: Penguin Group, 1985) pp. 46-47