Julia P. Herzberg

Monika Weiss 's Language of Lament: History, Memory, and the Body

in Recall: Roland Schefferski & Monika Weiss, Galeria BWA Zielona Góra & Muzeum Ziemi Lubuskiej, Poland, 2014

Monika Weiss is a transdisciplinary artist whose multifaceted works include drawing, performing, video, sound compositions, photography, and objects. In the broadest sense, the artist’s intermedia work executed in either private or public spaces addresses official and unofficial histories, time, memory, and the body. Phlegethon-Milczenie (2005), Leukos (2005), Drawing Lethe (2006), and Sustenazo (Lament II) (2010-2012), discussed in this essay, are constructed as nonlinear narratives in which the existential expression of lament or lamentation is central to the visual, sensorial, and physical discourse of each work.

Music is a primary language for the artist who listened daily to the piano as a child and then studied at the Warsaw Conservatory, where silence and listening were an obligatory part of her training. And, as soon noted, silence, which is also a language, became a core element in her performative process.[1] Weiss composes all the sound compositions in her work. Her body, a vehicle for expression and (silent) narration, stands for existence: its markings, absence—both are part of life. In an attempt to impart a sense of the complexity of Weiss’s thinking, performance, and practice, I will consider the various layers of her “unique fusion of media”[2] wherein memory, language, recorded sound, the moving image, thebody, time, and contingency are embedded.

In 2004 the Intergalerie in Potsdam, Germany invited Weiss to propose an exhibition that would openin 2005. Phlegethon-Milczenie was an installation of rare

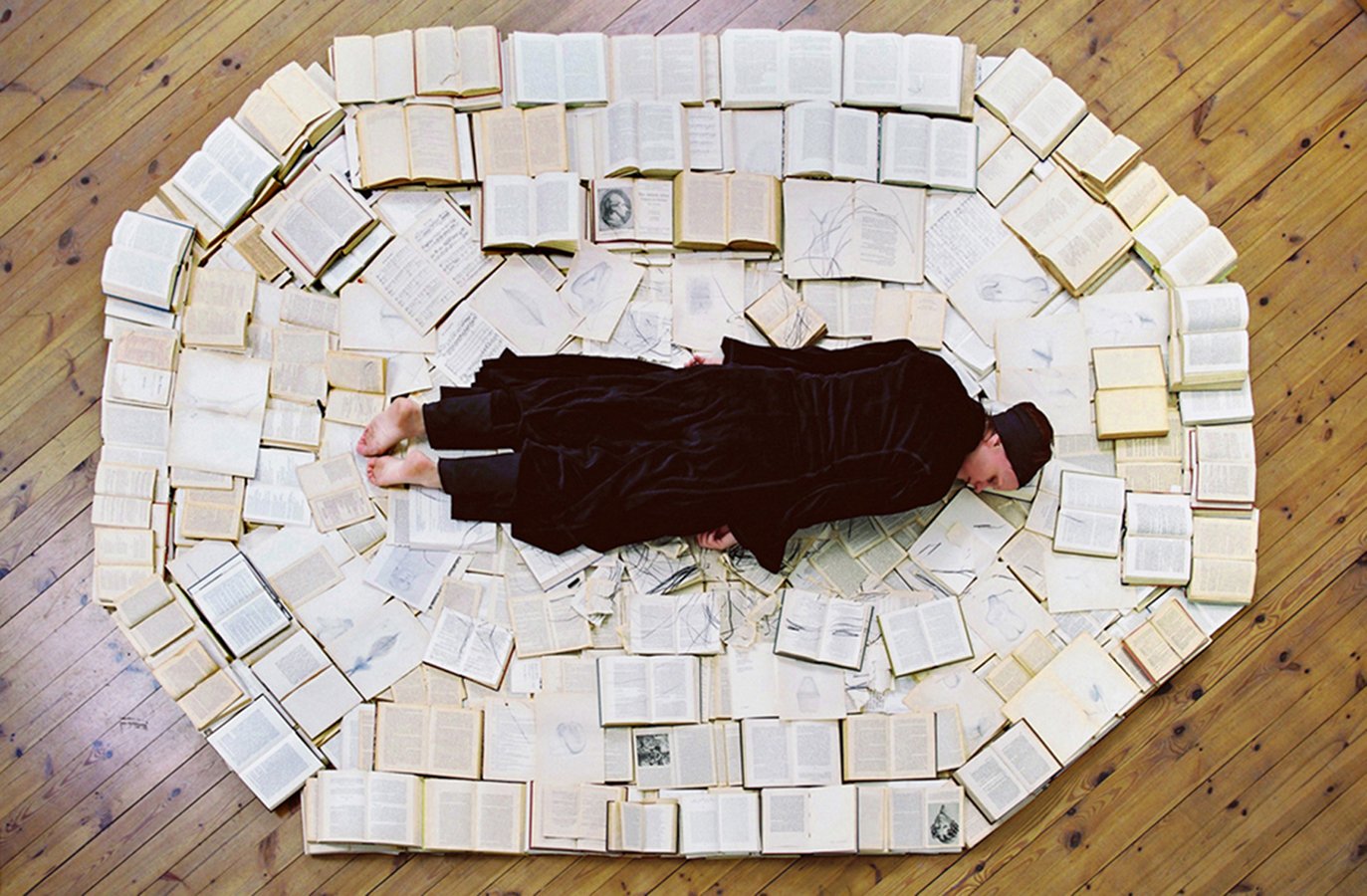

books containing literature, philosophy, and music, a performance by the artist on those objects, a projection of theinstallation, and a multi-channeled sound piece.[3] Phlegethon, the first word in the compound title, means River of Fire in Greek mythology, and Milczenie, the second word, is Polish and means “silence” or “an inability to speak.” The audience entered the exhibition in the first gallery, “Phlegethon,” where Weiss’s sound composition was projected together with a projection of her performing on the octagonal arrangement of open books in the second gallery, “Milczenie.”

In the Milczenie performance, which the artist repeated several times during the duration of the exhibition, she moved slowly and silently across the books with her eyes closed, in a meditative state, making marks with graphite and charcoal sticks around her body. Some of the books, by mostly German writers, philosophers, and composers, contained works that were either revered or destroyed by the Nazis. Their destruction depended on whether the regime deemed the authors degenerate or racially stained, and therefore not worthy contributors to high Germanic culture.

In preparing Phlegethon-Milczenie over the course of the year (2004) prior to its opening, the artist worked simultaneously on the sound composition, the part of the video that shows the burning of Thomas Mann’s Doctor Faustus: The Life of the German Composer Adrian Leverkuhn as Told by a Friend, the collection of vintage books, and the final design of the installation. Her steps for this particular installation-video- performance-sound composition are paradigmatic of her thinking and working processes in general. In different studios she recorded the voices of German speakers reading passages from Thomas Mann and the poetry of Paul Celan, as well as a male soprano singing passages a capella from Salve Regina by Giovanni Battista Pergolesi and Joseph Haydn’s Oratorio, and her own voice.[4]

The three-part composition of the video and sound is analogous to a classical musical composition, particularly in the historical period of Romanticism.[5] The first part shows the overhead view of the artist lying on the octagonal sculpture of the books drawing around her body accompanied by the sounds and some of the imagery of the burning book; the second part continues with the sounds of burning and some of the imagery of the burning book andalso introduces the voices of the German speakers reading passages from Paul Celan and Thomas Mann as well as the artist’s own voice in Polish and English; the third part shows closely filmed views of the burning book, Doctor Faustus, and accompanied by twelve irregularly overlaid and digitally altered tracks of the soprano’s voice singing a capella selected passages from Salve Regina by Giovanni Battista Pergolesi, and The Oratorio by Joseph Haydn.

Before going to Potsdam, Weiss designed the site-specific project in two galleries. In the"Milczenie" room the artist suspended an overhead video camera that filmed the octagonal installation of the books (including her several performances on them). The video camera, which has a recording device/system that accumulated filmed sequences over time, was connected via a system of cables to the “Phlegethon” room, where the audience first saw the projection of the book installation and the artist performing on several occasions in the “Milczenie” room.

During the two weeks following the opening, the artist selected fragments of raw footage from the camerarecordings and edited them into the first two parts of the video. Weiss then added the third part, the scene of Thomas Mann’s book, burning, which she had completed in New York. The final 18-minute video, determined by the duration of the sound composition, was subsequently projected throughout the exhibition in the “Phlegethon” room, with the exception of the instances when the artist returned to perform on the books. At those times the projection would again show the live view from the "Milczenie" room.[6] Weiss’s comments are notable in this regard: “There is a counterpoint quality of sound and image in this work in which I combined images of my body with the sounds of pages burning and images of fire with the sound of voices. I explore the important relationship between drawing and sound/music, focusing on the time-based and rhythmic qualities of drawing and the spatial and sculptural properties of music/sound. Both relate to the language of the body.” [7] These tropes elicit a play of time, memory, and a historical archive.

Phlegethon-Milczenie was included in Weiss’s first retrospective, Monika Weiss: Five Rivers (2005-2006), at Lehman College Art Gallery in Bronx, New York. The focus here, however, is on Leukos, an ancient Greek word meaning white, or light, brightness. The artist did the outdoor performance on sheets of white canvas sewn together and placed in the middle of the college campus. In this public performance, Weiss lay on an enormous canvas for three days, in different weather conditions, and drew marks around her body. In silence with her eyes closed, she slowly drew traces of herself moving across the white ground, leaving a record of her temporal presence. During the duration of the performative action, the curatorial staff invited people passing by to join the artist in silence and make their marks alongside of hers. In focusing on the moment and embracing the opportunity for chance, theparticipants, some still and others in movement, left traces of their bodies. In order to film that performance, Weiss had a camera installed on the rooftop of a building that captured the changing canvas as it gradually became darker due to a combination of the markings made by many participants and the rain that smeared the marks. Later the sound of the wind was recorded as part of the sound composition.[8] At the end of the performance, the canvas was moved into the main gallery, where its presence, according to the artist, felt like a shroud.

Drawing Lethe (2006), a very powerful public art project organized by The Drawing Center, was performed across from Ground Zero in the World Financial Center Winter Garden.[9] At the time, Ground Zero, where workerswere still digging for remains, was visible through the glass walls of the Winter Garden and thus a constant reminder of the September 11th attack on World Trade Center. Drawing Lethe was an especially poignant project that conveyed the symbolic feelings of lamentation through gestures of drawing and the sensorial reception of both recorded and live sound. Weiss performed on a huge white canvas as she had done in Leukos, slowly moving over the white ground in silence, drawing marks around her body, noting presence, movement, and life.[10] The artist

works with her prostrate body as symbolically against and opposing the notion of the heroic body, one historically in an upright position, often representative of power. She was assisted by a group of women who, dressed in black, also moved silently across the canvas leaving marks around their bodies with charcoal.

They in turn were joined by a cross-section of adults (even some children) who participated in the interactive work, allowing for the kind of contingency the artist sought. Some of the people sat on the canvas; others walked over it; and still others drew abstract lines around their bodies (some of the children drew figures). On the canvas, each person could hear the sound composition through multiple speakers that were invisibly installed under the area around the palm trees.[11] The sound components included mixed fragments of musical phrases sung by the artist’s opera vocalist and the whispering voices as well as the live sounds from the microphones and speakers that were hidden underground and installed around the trees. They were a metonymic reference to one of the two words in the title, Lethe, which means River of Oblivion in Greek mythology. The interactive performative work with sound was intended to thwart oblivion or amnesia. Drawing Lethe attempted to accomplish the opposite of what a security director of the World Financial Center Winter Garden feared prior to its installation: “I don’t know if we can allow this [work] because . . . people may remember.”

Sustenazo (Lament II), presented at the Museum of Memory and Human Rights in Santiago, Chile, was one of three videos presented at the Centre for Contemporary Art Ujazdowski Castle (CCA) in Warsaw in 2010. In Santiago the exhibition included an installation of vintage books, many with the artist’s drawings, together with medical objects. Similar to all of Weiss’s work, she directed, recorded, composed, and choreographed this work. The multiple meanings of Sustenazo (Lament II) are evoked through a sequence of imagery featuring the torso of a woman, an actress, moving slowly backward and forward in opposite directions, embodying in her gestures the expression of lament.xii Against this imagery are those of old maps of Europe, medical instruments used before and during World War II, a medical photograph of a woman’s chest, and a white-gloved hand moving gently over it. The visual narrative is dramatically enhanced by the artist’s musical composition, which includes recitations and deconstructions of literary texts. The visual narration excludes any specific references to the patients and medical staff of the Ujazdowski Hospital, who were forced to evacuate by the German Army (Wehrmacht) onto the streets of Warsaw within less than twenty-four hours’ notice, resulting in the deaths of 1,800 patients. Although the expulsion was a specific event that in part motivated the artist to communicate the devastating effects of totalitarian invasions and their inhuman consequences, lament became the carrier of the emotional states of grief and sorrow endured by humanity throughout time. Lament, a leit-motif coursing through the artist’s work, is a responsive gesture like a prayer or a plea, perhaps greater than speech, to oppositional states of war and peace; totalitarianism and freedom; sickness and health; life and death. From the memory of pain is born an infinite lamentthat struggles against an eternal return.[12]

Julia P. Herzberg, New York, 2014

[1] The artist’s mother was a pianist. At the Warsaw Conservatory (1974 to 1984), her ten- hour days were filled with both sounds and silence. In the early 1990s before coming to the U.S., the artist founded and played in the experimental music ensemble Small Warsaw Autumn, which recorded their improvised compositions.

[2] Guy Brett, “Time Being,” in Monika Weiss: Five Rivers (New York: Lehman College Art Gallery, City University of New York, 2006) p. 29.

[3] Intergalerie Potsdam was a contemporary art institution directed by Erik Bruinenberg, was part of Nicolaisaal Potsdam, a center for performing arts located in Potsdam, Germany.

[4] Paul Celan was born into a German-speaking Jewish family whose parents were victims of the Holocaust. Hisexperience of the Holocaust is a defining force in his poetry together with his use of a repetitive, condensed minimal use of language.

[5] For further elaboration on the artist’s methodological approach to video and sound compositions, see Monika Weiss in “Julia P. Herzberg Interviews Monika Weiss,” in Poza: On the Polishness of Polish Contemporary Art (Hartford,Connecticut: Real Art Ways, 2007), pp. 130, 131.

[6] Following the Potsdam video-performance-installation, the books were sent to the Kunsthaus Dresden (2006), where the artist also performed on them in the group exhibition You Won’t Feel a Thing; On Panic, Obsession, Rituality and Anesthesia. In 2007 the video-performance-installation was part of the group exhibition Forms of Classification: Alternative Knowledge and Contemporary Art at the Cisneros Fontanals Art Foundation (CIFO). The entire installation was acquired by CIFO for its collection.

[7] Monika Weiss in “Julia P. Herzberg Interviews Monika Weiss,” in Poza, pp. 131, 132.

[8] In 2006 Weiss presented the same canvas, then folded irregularly for the space of the Remy Toledo Gallery. From the thirty-five hours of video footage at Lehman, the artist created a film, a dual projection with a sound compositionconsisting of laments, sung by the same male soprano vocalist who sang in the Phlegethon-Milczenie composition, and sounds from the Lehman College campus including the wind. The laments were a combination of famous classical compositions together with Weiss’s own melodies, all overlapping, montaged, some reversed, to create an ocean of sound, with waves of chorus and wind-like sounds.

[9] Arts Brookfield was the organizing institution. Among the several costs they underwrote, they hired sixty helpers toorganize the flow of people around the perimeter of the installation. See http://brookfieldplaceny.com/arts-events

[10] Weiss and the women sewed sheets of canvas together, covered the floor and leaving the area around the tall palmtrees bare. The overall size of the canvas was approximately 150 by 200 feet.

[11] Before the opening of the public project, the artist composed the main sound composition over a period of several months. It was created from her various sound recordings and composed of many tracks that incorporated collagedfragments of musical phrases sung by her opera vocalist and the whispering voices. The predominant component of the composition were the sounds recorded on site by the artist as she was suspended from the glass ceiling of the Winter Garden with her sound recording equipment. Throughout the duration of the project the sound composition of 120 minutes was played on a continuous loop. In addition there was a delicate live sound, gathered by the microphones and mixed into the main sound coming through the speakers that added contingency to the overall sound environment.

[12] Etymologically, the word lament derives from Greek leros – “nonsense.” Webster’s New Collegiate Dictionary(C. & G. Merriam Company: Springfield, Mass., 1977), p. 645.

xiii Ricardo Brodsky and María José Bunster, “Introduction,” in Monika Weiss: Sustenazo (Lament II), general editor Julia P. Herzberg (Santiago, Chile: Museum of Memory and Human Rights, 2012), p. 3.

Julia P. Herzberg

Dr. Julia P. Herzberg’s curatorial and publishing career spans more than three decades. She has held curatorial positions at The Patricia & Phillip Frost Art Museum, Florida International University, Miami; El Museo del Barrio, New York City; and the Museum of Contemporary Hispanic Art, New York City. Dr. Herzberg has been an adjunct or consulting curator at museums that include El Museo de la Memoria y Derechos Humanos and The National Museum of Fine Art, both in Santiago, Chile; The Studio Museum in Harlem, New York; Lehman College ArtGallery, Bronx, New York; and the 8th, 9th, and 10th Havana Biennials. She has taught as a visiting professor, associate and adjunct professor and lecturer in universities in the U.S. and Chile. As a scholar and curator, Herzberg addresses questions of presence and absence; environmental issues; existential questions; political activism; modes of history; the problematics of representation; immigration and cross-border problems; exile and diaspora; political, social, and gender identities; war and violence; the field of DNA; the body as a political, social, historical, and racial agent; writing as imagery; and spirituality.