patrycja jastrzębska (conversation)

Salto Mortale of History: Sustenazo. Conversation with Monika Weiss

by Patrycja Jastrzębska

in Magazyn Sztuki Obieg, 2010

Patrycja Jastrzebska:

Some of your projects engage themes related to World War II and, by implication, the Nazi era, for example, Keimai 3 and Phlegethon-Milczenie. Your newest work, Sustenazo, also refers to that historical period, this time in connection with a specific place where you were part of the a-i-r laboratory program at the Centre of Contemporary Art (CCA) Ujazdowski Castle. Why are you interested in this particular theme?

Monika Weiss:

It seems to me that this period is an ongoing chapter in the history of modernity. As Zygmunt Bauman says, modernity is still in danger, and at the same time it creates this danger. A truly modern holocaust

differs from its prior incarnations in that its goal is not to kill the enemy but rather to create a better and cleaner society. Bauman speaks of a garden as a metaphor for modernity’s disposition to improve the

world, to compose it anew, to cleanse it—much like a gardener getting rid of weeds in the garden. Contemporary holocausts are related to systems of oppression on a massive scale and often result from the

politics of gardening.

PJ: I am interested in what you said about the politics of gardening and the motif of cleansing the world.

MW: Yes, in order to create a better one. The abrupt expulsion of the medical patients and staff from Ujazdowski Hospital by the German army is one example of such “cleansing.” Many other hospitals were

forcibly evacuated in 1944. Such political gestures are absurd from the point of view of humanism. Sustenazo recalls an example of such historical absurdity, yet at the same time it is a poetic and abstract

project. My work is built from multiple narratives in order to leave the meaning open to interpretation. For instance, you mentioned the work Keimai 3, which was commissioned in 2008 by the Frauenmuseum in Bonn. This piece is similar to Sustenazo in the way it’s built from seemingly incompatible elements, such as documents, books, and maps from the 1930s (related to the Berlin Olympics), but also a Chinese sword,

fencing equipment, and unusual drawings. Traces-lines drawn with charcoal appear on top of this material, connecting the archive into a single unit. Inspired by the medieval music of Hildegard von Bingen, I composed the soundtrack by overlapping different voices, layer upon layer, until they became an organic whole, almost a murmur. The viewer may remain on this abstract level or may go further into the political or historical theme, which refers to Helene Mayer, an Olympic champion in fencing and a German-Jewish athlete who represented Germany in 1936, even though her citizenship had been taken away from her the year before. Keimai 3 is therefore an example of a multi-thread composition. Sustenazo is not just a story of the forced hospital evacuation.

PJ: Exactly. The exhibition’s press release states that you were inspired only in part by the history of this place. What else inspired you?

MW: An important part of this work is the motif of lament as a form of expression outside language, confronted with the archive of a historical event—the expulsion of the hospital patients and staff. While

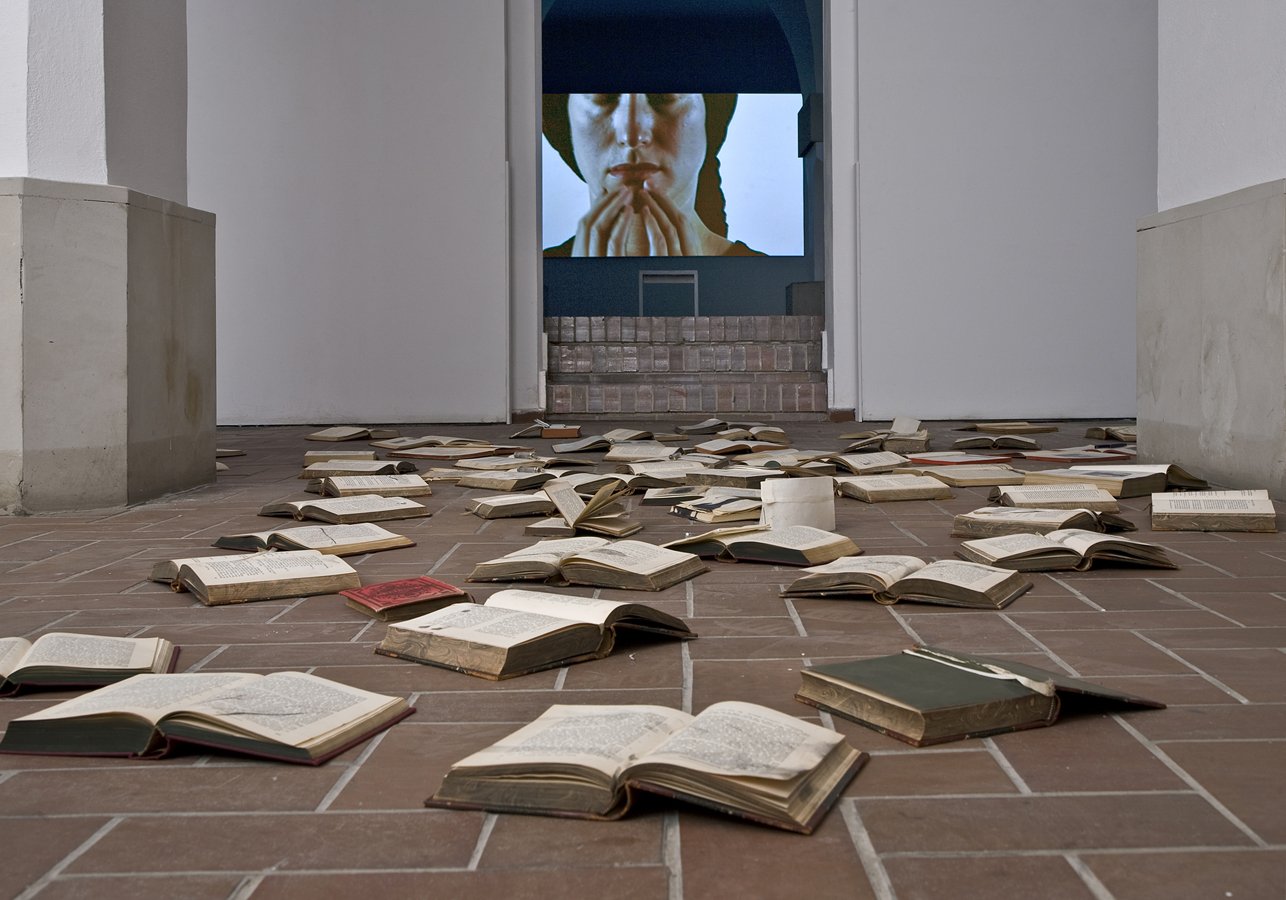

working on Sustenazo I searched for other non-historical motifs that would be outside the boundaries of a specific place and time. The three video projections in Sustenazo represent three basic narratives. The first video refers to the historical event through the filmed archive of documents and objects. In the second video a woman slowly performs a dance of lamentation. In the third piece we see a young woman repeating a jump forward and backward (in Italian, a salto mortale, or deadly somersault), as if she was forever suspended in a space outside time, which may suggest the motif of absurdity. There are also two sound compositions: Lament I, which accompanies the video projections, and Lament II—a corridor of sound through which one must pass in order to reach the rest of the exhibition. There is also an installation of eighty-eight books, a dozen medical instruments, drawings, a map of Europe, and a photograph of actrice Krystyna Janda’s bedroom.

PJ: That photograph seems to be starkly different from the rest of the project, creating a kind of a dissonance.

MW: In a way, the photograph is a reversed historical photograph. It is the memory of the place but seen now, today. It acquires meaning only in the context of the entire project, as the representation of the last

site where the expelled hospital arrived.i However, there is no information about where it is and why. I wanted to leave that question open. The photograph is in color, contemporary, cold, even though it’s a bedroom that displays clear signs of presence—crumpled sheets, a half-empty bottle with water by the bed.

PJ: For me this photograph is a different element in the work, something surprising, as if from another poetics and, of course, I immediately wanted to know what it represents, what is that bedroom.

MW: In Sustenazo various lines of narration intertwine as in a musical composition. Janda’s bedroom creates a dissonance, brings in another tone. Besides, the photograph was hung in the context of the drawings,

which have a more archaic appearance.

PJ: Do they come from your earlier projects?

MW: No, these are all new drawings—the three larger works Nosze as well as 105 small drawings on pages torn from Goethe’s books; all are part of Sustenazo. Nosze (“Stretchers”) were inspired by a conversation

with Krystyna Zalewska, who in 1944 was a thirteen-year-old nurse expelled with the rest of the hospital’s staff. During the several days of its exodus, the hospital had to make some stops. During one of them, Ms. Zalewska, together with another young nurse, was sent to the neighborhood to look for any wounded people. During their search they entered an abandoned building where they found a mountain of cabbage. Soon after that they were shot at, so they hid behind the cabbage, which they placed on the stretchers, and in this way managed to crawl back to the site where the hospital was temporarily located. Nosze were done on rice paper, which I placed on top of German stretchers from the 1940s, which I found in an auction. After laying down on them, I drew outlines around my body. I later transformed these outlines into the series of drawings. Furthermore, a single cabbage appears at some point in the video projection. Slowly unveiled layers of leaves are superimposed with pages from documents, which seem to burn, buried in sunlight.

PJ: It seems that taking inspiration directly from the Ujazdowski Hospital’s history distinguishes Sustenazo from your earlier projects, since none of them referred so explicitly to the history of the actual site.

MW: A few years earlier, Phlegethon-Milczenie in Potsdam (2005) already contained multiple layers of historical memory. It was my first work with authentic German books from before the war and with the

notion of fire. Hence initially I was hovering around this subject matter in a general way: fire, German books. I included fragments of poems by Paul Celan, who wrote in the language that pained him, in the language of his own oppressor, altering, infiltrating this language.

PJ: We are touching here upon the awareness of language, which is very important in your oeuvre.

MW: Language is an independent system, which remains in relation to what it describes, but at the same time departs from the meaning, replacing it with the “purity of language.” In my recent projects, lament

questions language. It is the moment of the collapse of language in face of the loss of the possibility to signify and to mean.

PJ: In Sustenazo you refer to a specific event, however you don’t take into account other, also traumatic events from the castle’s history, such as its demolition in the 1950s by the decision of the Polish People’s

Republic. Rather, you focus on a story from the time of the German occupation, concerning in fact many individuals. The evacuation of the hospital affected the lives of about eighteen hundred persons, so this

project is also speaking of the trauma of particular people.

MW: The archive of marginal experience is a story of life entangled in the game of power and authority by the accident of history. In my video, one cannot decipher the names of people participating in the exodus. I want to keep the privacy of actual people and their destinies. On the other hand, I respect their testimony, which one could call, after Agamben, an “enunciation.” The testimony of non-famous people, who bear

witness to their own encounter with the powerful, creates a track of another history, of another ethos.

PJ: Looking at your works from different series, sometimes one may have the impression that a given work recurs in several projects. Then you see that it is a completely different work, created for a specific project.

MW: In Sustenazo two periods of work have come together and, to some extent, two residencies. Partially I began working on some of the elements of this exhibition a year earlier during my residency in Berlin. There I recorded average Germans, asking them to read aloud passages from Goethe. I incorporated a fraction of those recordings into my installation Expulsion in Berlin. However, these voices found their final home in Sustenazo.

PJ: And you confronted these voices with the voices of evacuated Poles.

MW: Yes, mostly with one voice, that of an older woman, then the young nurse, whom I mentioned earlier. In Sustenazo her voice covers other, German voices, especially that of one woman who reads Goethe in her crystal-clear voice, which is being distorted by the words spoken by the nurse.

PJ: For most of your projects you also conduct extensive research?

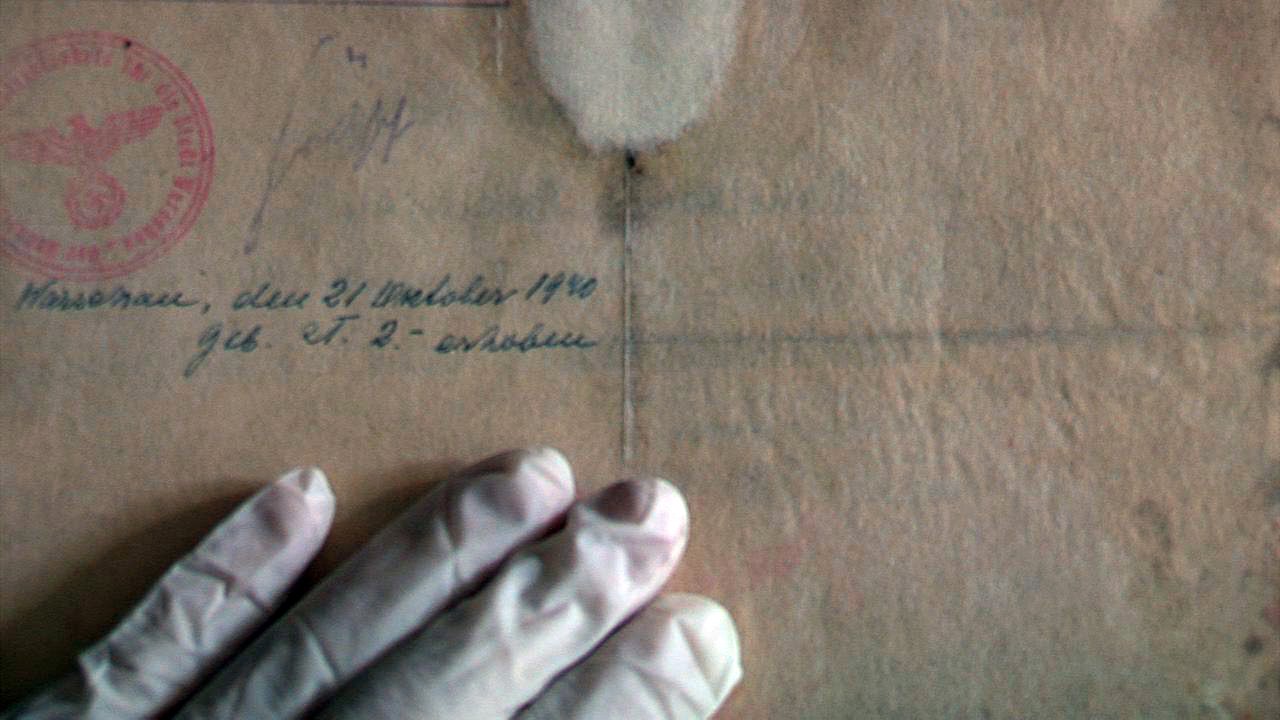

MW: Especially in this series I worked a little like an archivist and collaborated with archivists. I looked through and filmed all those documents. During my first residency at the CCA I worked with the Special

Archives section of the Medical Library. During my second visit I filmed selected archives in the Museum of the Warsaw Rising that are mostly unavailable to the public.

PJ: Did you include original documents in your project?

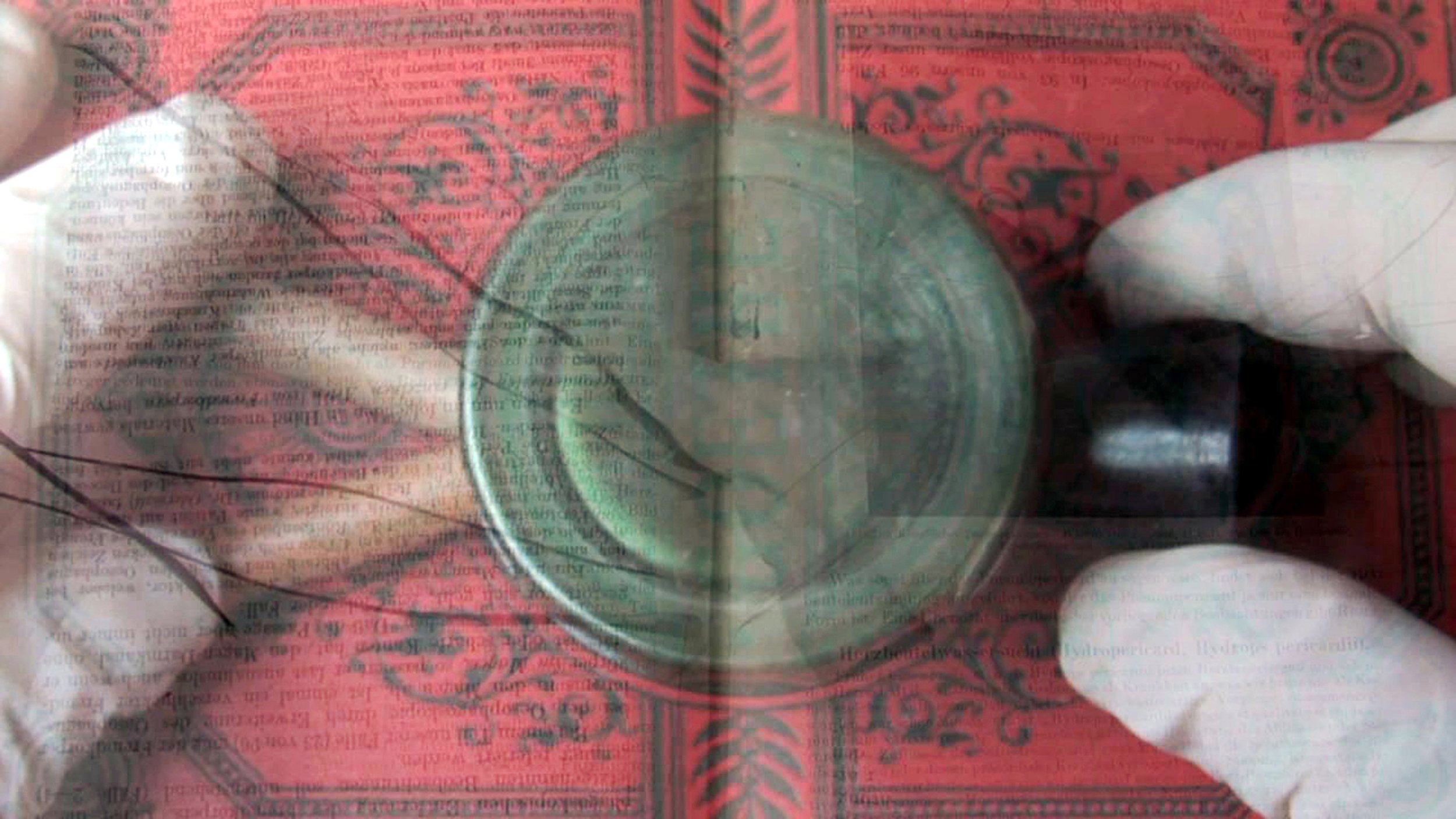

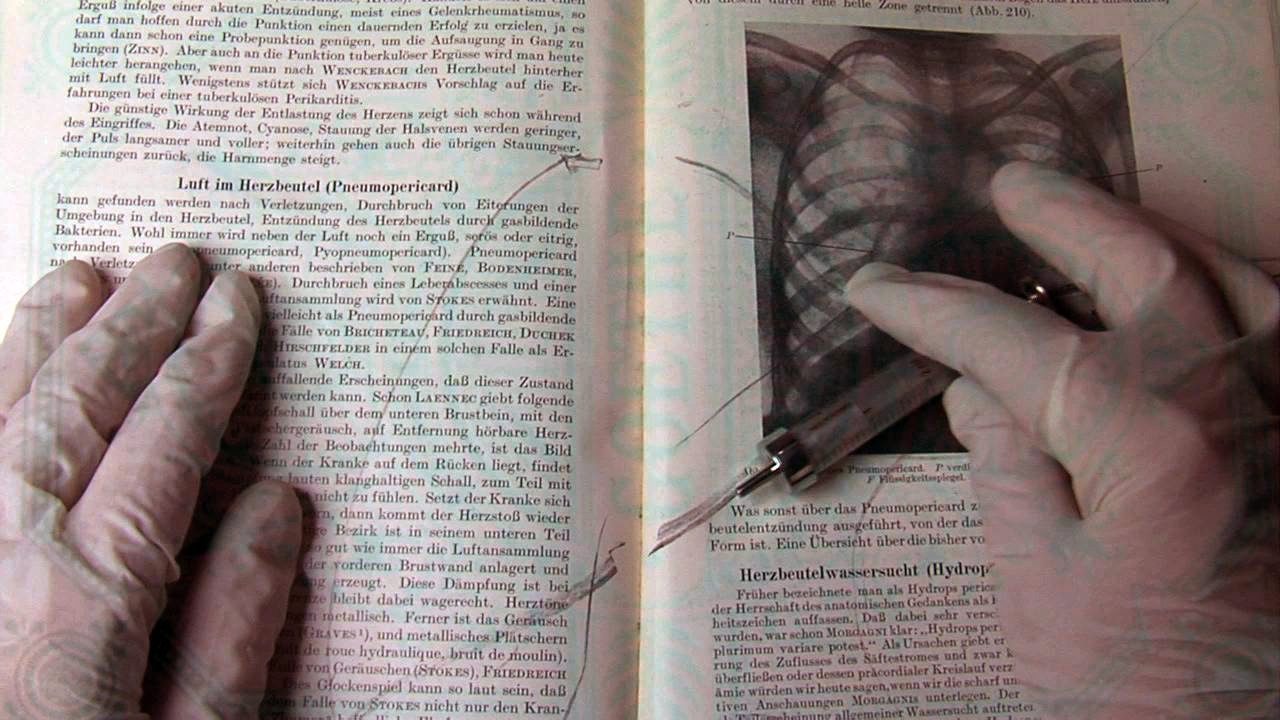

MW: The documents in Sustenazo appear as visual references in the video. It is a very close, intimate view. My hands appear wearing medical gloves, showing that I am touching the documents, that there is an

immediate contact.

PJ: With history?

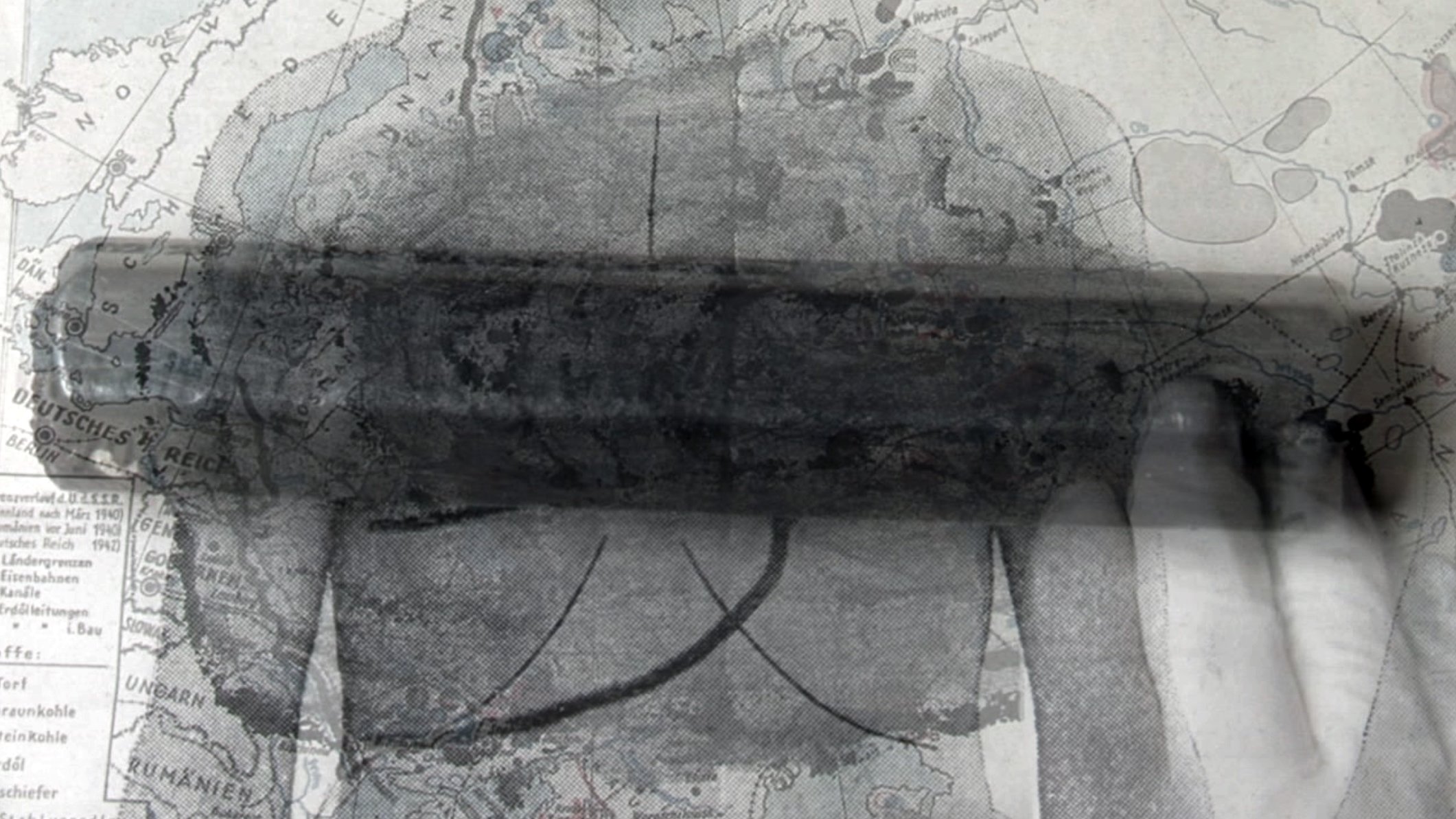

MW: Yes, with history. Hands wearing white gloves, which I had to wear while working with the archives, call to mind doctors’ hands. They bring to mind security, but at the same time danger. As a result of my CCA residency, I began collecting German medical books from before and during World War II as well as small medical instruments. Close-up views of those objects and also photos of anonymous bodies from the medical books appear in the video. A white-gloved hand smashes a chunk of charcoal, slowly covering a map of Europe with its powder as it draws, while the map gradually changes into a naked chest covered by medical drawings. I placed these open books and medical instruments on the ground, in the center of the installation, in a gallery below the level of the other galleries, so that you are looking at them from above. Alongside the medical books are also works of Goethe and Schiller published in the nineteenth century. They bear traces of ink and graphite. There are also scattered syringes, ampoules with surgical threads, a nurse’s bag. To get to that space one has to go through the sound corridor (Lament II) and through the rooms with video projections. The architecture of the castle’s cellars has inspired Sustenazo in a sense that the project is in a way a reversed journey of the hospital expelled out into the street; here you enter deep inside and under, returning, lower and lower, gradually sinking into the project.

PJ: And how are the voices of the evacuated people, Poles, related to the voices of Germans, who are reading Goethe? What did you intend to achieve with such a juxtaposition?

MW: As with the drawings made on pages from Goethe’s writings, the voices represent stains, traces that cannot be erased. Goethe’s voice can no longer exist without this other voice—the voice of the people who

were damaged by the games played by the power elite. I arranged the voices so that they overlap each other. It’s an open space for someone who enters the project, for your feelings, thoughts. What’s interesting

is that Germans receive this work in an entirely different way than, for instance, Poles; I am also wondering how this work will be received in New York, where it will be shown eventually.

PJ: I think that, in the context of your works, it is important to have cultural awareness. If we don’t have it, then we can’t completely enter into those works, and so we may lose something in our reception of them.

MW: I don’t completely agree, so I will speak through an example. There was a survey show at some point at the Lehman College Art Gallery (CUNY). The curator of the exhibition worried that because the gallery was located in the Bronx, the local population would have difficulty understanding the many layers of meaning in the works, and she wondered how to convey them to potential viewers.

PJ: This is generally a question troubling the entire contemporary art world.

MW: And yet, one day a group of local women came and looked at all the projects. One of them came to me and said that for her my art was about the breath of the world. Perhaps, then, there is a layer in

my work that is more primary, primordial even.

PJ: The titles of your works are always meaningful, and you often use Greek words, as for this project: Sustenazo in Greek means to lament, to whisper.

MW: To lament together, to whisper inaudibly.

PJ: The motif of lamentation appears in your video projection.

MW: Yes, this is also connected to the archaic, the primordial. The oldest known forms of lament were practiced by organized groups of women, who usually took off their headscarves and let their hair down in a

gesture of despair.

PJ: Which in fact appears in one of the videos.

MW: A woman very gradually takes off her headscarf. At a certain point the scarf returns to her head, tying her hair into a knot. The woman first bends down in one direction—perhaps she is falling, a little like a tree that bends in the wind. She returns, lifts her head up, and her hands move over her face, flowing. This repetition and mirroring of the movement also occur in the video of the acrobat who is forever jumping

backward and forward. In ancient rituals of lament, for instance, in ancient Greece, women became one body, one memory, and one act of mourning. In many traditions, lamentation is a response to death on a massive scale, often from a war. Sustenazo suggests collective reaction, sorrow, and remembering.

PJ: From what you say it seems like this is only women’s memory. But on the other hand there is also the masculine aspect—those who caused the evacuation were men. Man is the one who is the aggressor, who

fights, who sets up borders, at least in cultural terms. In this way, gender seems to be an important topic.

MW: Men—not just women—can participate in another reflective look at history. If we consider, for instance, that there is no gender (and if gender is difference), then I think such an anti-dualistic approach has more capacity to endanger so-called patriarchal forms of understanding, including understanding history, than the equality of the Other. Otherness seems problematic, because quite often it functions as a reason for massive crime. Hence I wouldn’t enclose this project inside so-called feminine sensibility. Taking responsibility, which the feminist Bracha Ettinger calls interconnectedness, now seems more crucial in terms of its revolutionary meaning for our culture than does equality—both sides having the same rights—which of course used to be, and in many regions of the world still is, necessary.

PJ: We’ve mentioned memory, history, but not the relation between memory and history. Many Polish and international artists are interested in this theme, for example, Balka, Jakubowicz, Polisiewicz, Boltanski, to name a few. It is a kind of reinterpretation of history, often touching its painful moments. It relates to the concept of postmemory, about which Marianne Hirsh writes: “Postmemory is a quality of the experience of those who grew up under a shadow of stories about events that happened before they were born. Their own memories had to give place to the histories of previous generations, formed under traumatic circumstances, which were never entirely comprehended or re-created.”

MW: Postmemory refers not only to events that took place before our birth, but also to the break between a living being and a speaking being, which is a break that marks an empty place. Lamenting voices permeate this emptiness, spanning between memory, which remembers only what has been said, and forgetting, which is only that which was never said. In contemporary art there are at least two evident approaches to history. One is more drastic, immediate, usurping a right to enter someone else’s life without asking. I feel more affinity with another approach, perhaps like Balka or Boltanski whom you mentioned, which assumes sensitivity and respect toward the people taking part in a project. It opens up, invites, but also protects. There is a great difference between an exchange and a one-sided taking.

PJ: I believe that, when an artist works with people who have suffered a traumatic event, it is important that after they have given something of themselves, they don’t feel as if something had been taken from them, as if something had been altered. Because a work is created and then has its own life, the artist moves on, produces other works, and the people who participated in the project remain themselves.

MW: I always try to keep in touch with the people whom I engage in a project. For example, in Anamnesis I worked with women in Portugal. After a while I returned to show them the video that resulted from the

project in which they took part.

PJ: An important element in your works is the motif of the body. The experience of one’s body can be a journey to get to know oneself, can be a form of meditation. You show it in many of your earlier works, for

instance, in Ennoia (2002), where you remained immersed in a chalice with water for many hours. In an interview you once said that the audience was leaving the museum, which was closing, and you were still in

that chalice. At any rate, here you abstain from performance. As is characteristic for your work, in Sustenazo you combine different media—sound, drawing, installation, video—but there is no performance, and your body appears only through your gloved hands. Instead you employ the body of another person.

MW: In Sustenazo another woman appears—my alter ego. The gesture of lamentation is performed by my extension, by this other yet not necessarily different person. Traces of the presence of my own body, my

actions, occur in the touching of the books, documents, and medical instruments. These are my hands, but they are almost anonymous. There are also other traces-drawings, which involve a private form of touching. Perhaps on some level Sustenazo doesn’t depart much from my previous works, because this melting or merging into “others” or into matter (as into water, in Ennoia) works as “crossing out,” erasing one’s own presence. This is also articulated, for example, in my series of public-interactive projects, such as Drawing Lethe at the Winter Garden, in the World Financial Center, across from Ground Zero.

PJ: In the case of the medical motif related to healing, which a hospital is supposed to provide, in this project there is a confrontation with the body and in general with human beings, who are perceived by the Nazis in an objectified way.

MW: Perceiving the body as biological (biopolitics) creates a situation where a life has no value as such. Statistics make it possible to look at human existence as biological existence with political consequences, but this has nothing to do with empathy. This approach appears among others in Nazi policies and has its roots in European modernity, with its functional thinking on a grand scale. Bodies become meaningful only as connected to larger systems. Hence the body is a national body, an economic or geographic body. In my recent works the body is a continuously changing space. It is a membrane between “self” and the external

“world,” a presence through trace. I try to show that presence in smallness, in that which is marginal, yet which is elevated into the realm of meaning through its encounter with history.

PATRYCJA JASTRZĘBSKA: Niektóre Twoje realizacje podejmują tematykę II wojny światowej i dotykają wątku nazistowskiego, m.in. odwoływałaś się do nich w Kemai 3 czy też Phlegethon-Milczenie. W najnowszej pracy Sustenazo także przywołujesz ten okres, aczkolwiek powiązany z miejscem, w którym odbywałaś rezydencję w ramach programu a-i-r laboratory w CSW. Dlaczego akurat ten wątek cię interesuje?

MONIKA WEISS: Wydaje mi się, że ten okres jest nie do końca zamkniętym rozdziałem historii nowoczesności. Jak mówi Zygmunt Bauman, jest to nowoczesność, która nadal jest zagrożona, a jednocześnie sama powoduje to zagrożenie. Prawdziwie nowoczesna zagłada różni się od swoich wcześniejszych wcieleń tym, że jej celem nie jest zabicie przeciwnika, lecz stworzenie lepszego i „czystszego" społeczeństwa. Bauman mówi o ogrodzie, to znaczy o nastawieniu współczesności na udoskonalanie, na komponowanie świata od nowa, wyczyszczanie; to trochę tak, jakby ogrodnik usuwał chwasty w swoim ogrodzie. Współczesne holokausty powiązane są z systemami opresji na masową skalę i często są wynikiem polityki „ogrodnictwa".

PATRYCJA JASTRZĘBSKA: Zainteresowało mnie to, co powiedziałaś o polityce ogrodnictwa i wątku czyszczenia świata... .

MONIKA WEISS: ...w celu stworzenia lepszego. Przykładem takiego czyszczenia było wyrzucenie Szpitala Ujazdowskiego przez niemiecką armię - a nie był on jedynym szpitalem wyrzuconym w 1944 r. Są to gesty polityczne, z punktu widzenia humanizmu absurdalne. Sustenazo przywołuje przykład takiej absurdalnej historii, a jedonocześnie jest projektem poetyckim, abstrakcyjnym. W moich pracach łączę narracje i wątki tak, by ich znaczenie pozostało otwarte na interpretacje. Na przykład praca Keimai 3, o której wspomniałaś, a która powstała dla Frauenmuseum w Bonn, jest podobna trochę do Sustenazo, ponieważ składa się z elementów pozornie nieprzystających do siebie, takich jak dokumenty, książki oraz mapy z lat 30. związane z Olimpiadą w Berlinie, a także miecz chiński, sprzęt szermierczy, pojedyncze rysunki. Na tym materiale pojawiają się ślady-linie rysowane węglem, łącząc to archiwum w jedną całość. Dźwięk zainspirowany średniowiecznym utworem Hildegard von Bingen skomponowałam, nakładając kolejne warstwy głosów tak, że stały się organiczną całością, nieomal szumem. Widz może pozostać na tym poziomie abstrakcyjnym lub może zagłębić się w wątek polityczno-historyczny nawiązujący do postaci Helen Mayer, mistrzyni olimpijskiej w szermierce i niemieckiej Żydówki, która reprezentowała Niemcy w 1936 r., choć została pozbawiona obywatelstwa w 1935 r. Keimai 3 jest więc przykładem wielowątkowej kompozycji. Sustenazo nie jest tylko opowieścią o szpitalu wygnanym...

PATRYCJA JASTRZĘBSKA: Właśnie. W nocie prasowej jest powiedziane, że tylko częściowo inspirowałaś się historią tego konkretnego miejsca; co wobec tego jeszcze cię zainspirowało?

MONIKA WEISS: Ważną częścią tej pracy jest motyw lamentu jako formy wypowiedzi poza językiem, zestawionej z archiwum wydarzenia historycznego, jakim było wyrzucenie szpitala. Podczas pracy nad Sustenazo szukałam innych wątków, które byłby poza granicami konkretnego miejsca i czasu. Trzy projekcje wideo w Sustenazo reprezentują trzy podstawowe narracje. Pierwsze wideo nawiązuje do wydarzenia historycznego poprzez sfilmowane archiwum dokumentów i obiektów. W drugim kobieta wykonuje powolny taniec lamentu. W trzecim widzimy młodą kobietę powtarzającą skok w przód i w tył, salto mortale, jakby na zawsze zawieszoną w przestrzeni poza czasem, co być może sugeruje motyw absurdalności. Są też dwie kompozycje dźwiękowe: Lament I, towarzyszący wideo, oraz Lament II - korytarz dźwięku, przez który musimy przejść, by dojść do pozostałej części wystawy. Jest też instalacja z osiemdziesięciu ośmiu książek i kilkunastu instrumentów medycznych, rysunki, mapa Europy i fotografia sypialni Krystyny Jandy.

PATRYCJA JASTRZĘBSKA: Fotografia ta właściwie odcina się od reszty projektu, stwarza pewien dysonans.

MONIKA WEISS: To zdjęcie jest w pewnym sensie odwrotnością historycznej fotografii. Jest to postpamięć miejsca teraz, dzisiaj. Fotografia ta nabiera znaczenia dopiero w kontekście całego projektu jako przedstawienie ostatniego miejsca gdzie wygnany szpital dotarł [1]. Nie ma jednak podanej odpowiedzi, gdzie to jest i dlaczego. Chciałam zostawić ten znak zapytania. Zdjęcie jest w kolorze, współczesne, zimne, mimo że jest to sypialnia zawierająca wyraźne ślady obecności - pomięta pościel, niedopita woda w butelce przy łóżku.

PATRYCJA JASTRZĘBSKA: Dla mnie ta fotografia to taki inny element z całości pracy, coś zaskakującego, trochę z innej poetyki i oczywiście od razu zrodziło mi się pytanie, co to zdjęcie przedstawia, co to za sypialnia.

MONIKA WEISS: W Sustenazo linie różnych narracji splatają się trochę jak w kompozycji muzycznej. Sypialnia Jandy stwarza dysonans, wprowadza inne brzmienie. Poza tym zdjęcie powieszone zostało w kontekście rysunków, które mają bardziej archaiczny wyraz.

PATRYCJA JASTRZĘBSKA: Czy one pochodzą z twoich realizacji wcześniejszych?

MONIKA WEISS: To są nowe rysunki - zarówno trzy duże prace Nosze, jak i sto pięć małych rysunków na stronach pism Goethego; wszystkie wchodzą w skład Sustenazo. Nosze były zainspirowane rozmową z Krystyną Zalewską, która w 1944 r. była trzynastoletnią dziewczynką i jako sanitariuszka została wyrzucona ze szpitalem. Podczas kilkudniowej wędrówki szpital musiał się zatrzymywać i podczas jednego z takich przystanków pani Krystyna wraz z inną sanitariuszką zostały wysłane z noszami, aby szukać rannych ludzi w okolicy. Podczas poszukiwań weszły do opustoszałego budynku, w którym znalazły górę główek kapusty.

W tym czasie do nich strzelano, więc schowały za tą kapustą, położoną na noszach, i jakoś doczołgały się z powrotem do miejsca, gdzie szpital się tymczasowo rozlokował. Rysunki Nosze zostały wykonane na papierze ryżowym pokrywającym niemieckie nosze z lat 40., które znalazłam na aukcji. Położyłam się na nich i rysowałam wokół własnego ciała. Te obrysy później przekształciły się w serię rysunków. Również pojedyncza główka kapusty pojawia się w pewnym momencie w jednej z projekcji wideo. Powoli odkrywane warstwy liści nakładają się na strony dokumentów, które wydają się płonąć, spowite światłem słonecznym.

PATRYCJA JASTRZĘBSKA: Wydaje się, że czerpanie inspiracji bezpośrednio z historii Zamku Ujazdowskiego odróżnia projekt Sustenazo od twoich poprzednich realizacji, bo żadna z nich nie odwoływała się tak bezpośrednio do historii konkretnego miejsca?

MONIKA WEISS: Projekt Phlegethon-Milczenie w Poczdamie (2005) zawierał już wiele warstw pamięci historycznej. To była pierwsza moja praca z autentycznymi książkami niemieckimi sprzed wojny i z ideą ognia. Krążyłam więc wokół tego tematu najpierw bardzo ogólnie: ogień, książki niemieckie. Pojawiły się fragmenty wierszy Paula Celana, który pisał w języku, który go bolał, w języku własnego oprawcy, naruszając, infiltrując ten język.

PATRYCJA JASTRZĘBSKA: Dotykamy tu także świadomości języka, który w twojej twórczości jest bardzo ważny.

MONIKA WEISS: Język jest niezależnym systemem, który pozostaje w relacji do tego, co opisuje, ale jednocześnie odchodzi od znaczenia, zastępując je „czystością języka". W moich ostatnich projektach lament kwestionuje język. Jest momentem załamania się języka wobec utraty możliwości oznaczania i znaczenia.

PATRYCJA JASTRZĘBSKA: W Sustenazo odwołujesz się do konkretnego zdarzenia, nie bierzesz natomiast pod uwagę innych, także traumatycznych wydarzeń z życia Zamku, jak chociażby wyburzenie go w latach 50. decyzją władz PRL, tylko historię z lat okupacji, dotyczącą przecież także pojedynczych osób. Tutaj podczas ewakuacji szpitala zostało wyrzuconych około 1800 osób, więc to jest też dotknięcie traumy poszczególnych osób.

MONIKA WEISS: Archiwum marginalnego doświadczenia to historia życia uwikłanego w rozgrywkę sił lub władzy poprzez przypadek historyczny. Nie można przeczytać nazwisk ludzi uczestniczących w wygnaniu w moim wideo, pragnę zachować prywatność konkretnych osób i ich losów. Z drugiej strony szanuję ich świadectwo, które można nazwać za Agambenem „ennunciation", czyli „wypowiedzeniem". Świadectwo ludzi niesławnych, którzy są świadkami swojego własnego spotkania z siłą, tworzy szlak innej historii, innego etosu.

PATRYCJA JASTRZĘBSKA: Oglądając twoje prace z różnych cykli, czasem można odnieść wrażenie, że dana praca przewija się w kilku realizacjach. Jednak okazuje się, że jest to zupełnie nowa praca, powstała do konkretnego projektu.

MONIKA WEISS: W Sustenazo połączyły się dwa okresy pracy i także, do pewnego stopnia, dwie rezydencje. Częściowo nad niektórymi elementami tej wystawy zaczęłam pracować rok wcześniej podczas rezydencji w Berlinie. Tam nagrywałam przeciętnych Niemców, prosząc, by czytali na głos fragmenty z Goethego. Jakiś ułamek z tych nagrań wykorzystałam do instalacji Expulsion w Berlinie. Lecz te głosy odnalazły swoje docelowe miejsce w Sustenazo.

PATRYCJA JASTRZĘBSKA: I głosy te skonfrontowałaś z głosami ewakuowanych Polaków...

MONIKA WEISS: Głównie z jednym głosem - kobiety, sanitariuszki, o kórej wspomniałam wcześniej, pani Krystyny. W Sustenazo jej głos przykrywa inne głosy niemieckie, zwłaszcza Niemki, która czyta Goethego czystym, klarownym glosem, który jest zakłócany właśnie słowami wypowiadanymi przez sanitariuszkę...

PATRYCJA JASTRZĘBSKA: Podobno niemal do każdego projektu przeprowadzasz intensywny research.

MONIKA WEISS: Zwłaszcza w tej serii projektów pracuję trochę jak archiwista i współpracuję z archiwistami. Przeglądam, filmuję te wszystkie dokumenty. Podczas pierwszego pobytu na rezydencji w CSW pracowałam na Zbiorach Specjalnych Biblioteki Medycznej. Podczas drugiej wizyty filmowałam wybrane i raczej niedostępne dla publiczności archiwa Muzeum Powstania.

PATRYCJA JASTRZĘBSKA: Włączyłaś do projektu oryginalne dokumenty?

MONIKA WEISS: Dokumenty w Sustenazo pojawiają jako odnośniki wizualne w obrazie wideo. Jest to bardzo bliski, bardzo intymny wgląd, pojawiają się moje ręce ubrane w medyczne rękawiczki, pokazuję, że ich dotykam, jest to bezpośredni kontakt...

PATRYCJA JASTRZĘBSKA: Z historią?

MONIKA WEISS: Tak, z historią. Ręce ubrane w białe rękawiczki, które musiałam zakładać, pracując z archiwaliami, przywołują skojarzenie z rękami lekarzy. Kojarzą się z ochroną, a jednocześnie z niebezpieczeństwem. W wyniku rezydencji w CSW zaczęłam zbierać niemieckie książki medyczne z czasów przedwojennych i wojennych oraz drobne instrumenty medyczne. Zbliżenia tych obiektów oraz zdjęcia anonimowych ciał z medycznych książek pojawiają się w wideo. Moja ręka ubrana w białą rękawiczkę rozgniata węgiel, powoli pokrywając nim mapę Europy, rysując, podczas gdy mapa powoli przemienia się w obnażoną klatką piersiową pokrytą rysunkiem lekarskim. Umieściłam te otwarte książki i przybory medyczne na ziemi, w centrum instalacji, w pomieszczeniu, które jest poniżej poziomu pozostałych sal, więc patrzysz na nie z góry. Obok medycznych książek są tam także dzieła Goethego i Schillera wydane w XIX wieku. Są na nich ślady tuszu i grafitu. Znalazły się tam także porozrzucane strzykawki, ampułki z nićmi chirurgicznymi, torba pielęgniarki. Do tego miejsca trzeba dojść poprzez korytarz dźwięku (Lament II) i poprzez sale z projekcjami wideo. Architektura podziemi Zamku zainspirowała Sustenazo w tym sensie że projekt ten jest jakby podróżą i jednocześnie odwrotnością wyrzucenia szpitala na ulicę: tutaj wchodzisz wgłąb, z powrotem, coraz niżej, stopniowo zagłębiasz się w projekt.

PATRYCJA JASTRZĘBSKA: A jak się mają głosy ludzi ewakuowanych, Polaków, do głosów Niemców, którzy czytają Goethego, co chciałaś przez to zderzenie uzyskać?

MONIKA WEISS: Podobnie jak rysunki na stronach utworów Goethego, głosy reprezentują plamy, ślady, które są niewymazywalne. Słowa Goethego już nie mogą istnieć bez tego innego głosu - głosu ludzi, którzy byli poszkodowani poprzez rozgrywki siły. Skomponowałam je tak, by się nakładały na siebie w tych nagraniach. Jest to otwarta przestrzeń dla kogoś, kto w nią wchodzi, dla twoich uczuć, myśli. Co jest ciekawe, Niemcy odbierają to zupełnie inaczej niż np. Polacy; jestem też ciekawa, jak ten projekt zostanie odebrany w Nowym Jorku, gdzie będzie pokazywany.

PATRYCJA JASTRZĘBSKA: Wydaje mi się, że w kontekście twoich prac świadomość kulturowa jest ważna, jeśli jej nie mamy, to nie do końca możemy „wejść" w te prace, przez co tracimy na odbiorze.

MONIKA WEISS: Nie do końca się z tym zgodzę, więc dam ci przykład. Kiedy odbyła się moja retrospektywna wystawa w Lehman College Art Gallery (CUNY), kuratorka wystawy bardzo się martwiła, że ze względu na położenie muzeum w Bronxie tamtejsi ludzie będą mieli trudność z odbiorem tych wielu warstw znaczeniowych i jak to przekazać laikom.

PATRYCJA JASTRZĘBSKA: To jest w ogóle pytanie dotyczące całej sztuki współczesnej...

MONIKA WEISS: Jednak kóregoś dnia przyszła grupa miejscowych afroamerykańskich kobiet, które obejrzały wszystkie projekty. Jedna z nich podeszła do mnie i powiedziała że dla niej moja sztuka opowiada o oddechu świata. Być może jest więc także taka warstwa moich prac, która jest bardziej pierwotna.

PATRYCJA JASTRZĘBSKA: Zawsze tytuły twoich prac są znaczące, często sięgasz do greki, jak zresztą w tym projekcie: Sustenazo to z greki lamentować, wzdychać...

MONIKA WEISS: Lamentować razem, wzdychać bezsłyszalnie.

PATRYCJA JASTRZĘBSKA: Wątek lamentu pojawia się na jednej z trzech projekcji wideo.

MONIKA WEISS: Tak, to także jest związane z archaicznością, pierwotnością. Najstarsze znane formy lamentu były praktykowane przez zorganizowane grupy kobiet, które zwykle zdejmowały swoje chusty i rozpuszczały włosy w geście rozpaczy.

PATRYCJA JASTRZĘBSKA: Co się pojawia w jednej z projekcji wideo.

MONIKA WEISS: Kobieta bardzo powoli zdejmuje chustę. W pewnym momecie chusta sama powraca na jej głowę, wiążąc z powrotem w węzeł jej włosy. Kobieta kłania się najpierw w jedną stronę, być może upada, trochę jak drzewo, które przegina się od wiatru. Powraca, podnosi się w górę, jej dłonie wędrują po twarzy, spływają. To powtórzenie i odbicie ruchu jak w lustrze pojawia się także w projekcji z akrobatką skaczącą w przód i w tył bez końca. W rytuale starożytnego lamentu, np. w antycznej Grecji, kobiety stają się jednym ciałem i jedną pamięcią, jednym żalem. W wielu tradycjach lament jest odpowiedzią na masową śmierć, a więc często na wojnę. Sustenazo sugeruje wspólną reakcję, żal i pamiętanie.

PATRYCJA JASTRZĘBSKA: Z tego, co mówisz, wynika, że jest to przede wszystkim pamięć kobieca. Ale z drugiej strony jest też aspekt męski - sprawcami ewakuacji szpitala byli mężczyźni. A mężczyzna to ten, kto jest agresorem, kto walczy, wyznacza granice, przynajmniej w kulturowym rozumieniu. Z tego wyłania się wątek gender.

MONIKA WEISS: Mężczyzna może mieć udział w innym spojrzeniu na historię, to nie jest tylko właściwość kobieca. Jeżeli np. założymy, że nie ma gender (o ile gender jest różnicą), to wydaje mi się, że takie antydualistyczne myślenie bardziej zagraża skostniałym, tak zwanym patriarchalnym formom rozumienia (w tym także rozumienia historii), niż samo podkreślanie równouprawnienia Innego. Inność jest problematyczna, ponieważ często funkcjonuje jako wytłumaczenie lub umożliwienie masowej zbrodni. Nie zamykałabym więc tego projektu wewnątrz wrażliwości tak zwanej kobiecej. Przyjmowanie odpowiedzialności, współodczuwanie, które np. feministka Bracha Ettinger nazywa interconnectedness, wydaje się w tej chwili istotniejsze w sensie swojego znaczenia rewolucyjnego dla naszej kultury, niż podkreślanie, że obie strony mają takie same prawa, co oczywiście było i ciągle jeszcze jest niezbędne w wielu rejonach świata.

PATRYCJA JASTRZĘBSKA: Wspominałyśmy o pamięci, o historii, jednak nie tylko o relacji pamięć - historia. Wielu polskich i światowych artystów interesuje ten wątek, by wymienić Bałkę, Jakubowicza, Polisiewicz czy Boltańskiego. Jest to pewna reinterepretacja historii, dotykanie często bolesnych jej momentów. To łączy się też z koncepcją postpamięci, o której pisze Marianne Hirsch: Postpamięć jest cechą doświadczenia tych, którzy wzrastali w cieniu opowieści o zdarzeniach, które rozegrały się przed ich narodzeniem. Ich własne wspomnienia musiały ustąpić miejsce historiom poprzednich pokoleń, ukształtowanym w traumatycznych okolicznościach, które nigdy nie zostały do końca zrozumiane ani odtworzone.

MONIKA WEISS: Dla mnie postpamięć odnosi się nie tylko do wydarzeń sprzed naszych narodzin, ale także do pewnego rozłamu, przerwania między żyjącym istnieniem i bytem mówiącym, które to przerwanie zaznacza puste miejsce. To puste miejsce powinno być nazwane nowym archiwum, wpisującym się w pustkę pozostałą po znaczeniu. Lamentujące głosy przenikają tę pustkę, rozpościerającą się między pamięcią, która pamięta tylko to, co było powiedziane, a zapomnieniem, które jest tylko tym, czego nigdy nie powiedziano. W sztuce współczesnej są widoczne co najmniej dwa podejścia do historii. Jedno bardziej drastyczne, bezpośrednie, które uzurpuje sobie prawo do wejścia w czyjeś życie bez pytania. Ja czuję pokrewieństwo raczej z tym drugim, innym podejściem, jak u Boltańskiego czy u Bałki, o których wspomniałaś, które zakłada pewną delikatność i szacunek wobec osób biorących udział w projekcie, otwiera, zaprasza, ale także chroni.

PATRYCJA JASTRZĘBSKA: Wydaje mi się, że przy pracy z uczestnikami traum jest bardzo ważne, żeby oni po takim kontakcie, w którym coś jednak dali z siebie, nie czuli, jakby im coś zabrano, jakby coś zostało naruszone. Bo projekt powstaje i potem żyje swoim własnym życiem, artysta idzie dalej, realizuje kolejne projekty, a oni z tym zostają, zostają ze sobą.

MONIKA WEISS: Zawsze próbuję utrzymywać kontakty z osobami, które zaangażowałam w projekcie. Np. w projekcie Anamnesis pracowałam z kobietami W Portugalii. Po pewnym czasie powróciłam do nich, aby pokazać im pracę wideo będącą efektem projektu, w którym uczestniczyły.

PATRYCJA JASTRZĘBSKA: Ważnym elementem twoich realizacji jest wątek ciała. Doświadczenie własnego ciała może być drogą do poznania siebie, może być formą medytacji. Pokazujesz to w wielu wcześniejszych projektach, np. w performansie Ennoia (2002), gdzie pozostałaś zanurzona na wiele godzin w kielichu wypełnionym wodą. I w jakimś wywiadzie wspominałaś, że widzowie opuszczali muzeum, które zamykano, a ty pozostawałaś nadal w tym kielichu. W Sustenazo rezygnujesz z performansu. Co jest dla ciebie charakterystyczne, w Sustenazo łączysz media: jest dźwięk, rysunek, instalacja, wideo, ale tutaj nie ma performansu, a twoje ciało pojawia się jedynie poprzez dłonie ubrane w rękawiczki. Z kolei w wideo wykorzystałaś ciało innej osoby.

MONIKA WEISS: W Sustenazo pojawia się inna kobieta, moje alter ego. Gest lamentu jest wykonany przez moje przedłużenie, przez tę drugą, choć niekoniecznie lub nie całkowicie inną, osobę. Ślady obecności mojego ciała, moje działanie, pojawia się w formie dotyku książek, dokumentów i przyborów medycznych. To są moje ręce, które są nieomal anonimowe. Są też ślady-rysunki, które też są prywatnym dotykiem. Myślę, że na pewnym poziomie Sustenazo nie odbiega aż tak daleko od moich poprzednich prac, ponieważ to wtapianie się w „innych" lub w materię (np. w wodę w Ennoi) funkcjonuje jako przekreślanie, zamazywanie swojej własnej obecności. To jest też artykułowane np. w mojej serii publicznych instalacji-interaktywnych rysunków, takich jak Drawing Lethe w Winter Garden, WFC, tuż obok Ground Zero.

PATRYCJA JASTRZĘBSKA: A jeśli chodzi o wątek medyczny, który łączy się z uzdrawianiem - szpital ma służyć uzdrawianiu i w tym projekcie pojawia się konfrontacja z ciałem i w ogóle człowiekiem postrzeganym przez nazistów bardzo przedmiotowo.

MONIKA WEISS: Postrzeganie ciała jako ciała biologicznego, biopolitics, powoduje, że bare life („nagie życie") nie ma znaczenia jako takie. Numer (statystyka) to patrzenie na istnienie ludzkie jako na istnienie biologiczne, które ma polityczne konsekwencje, ale to nie ma nic wspólnego z empatią. Taki stosunek do ludzkiego życia pojawia się m.in. w polityce nazistów, Biopolitics ma rodowód związany z europejskim modernizmem, z myśleniem funkcjonalnym na ogromną skalę. Ciała nabierają znaczenia dopiero jak zostaną powiązane w większe całości systemowe. Czyli ciało jako ciało narodowe, ciało jako ciało ekonomiczne lub geograficzne. W moich pracach z ostatnich lat ciało jest stale zmieniającą się przestrzenią. Jest membraną pomiędzy „ja" a „światem" zewnętrznym, jest obecnością poprzez ślad. Staram się pokazać tę obecność w małości, w tym, co marginalne, a jednak podniesione w rejony znaczenia poprzez spotkanie z historią.

[1] Obecny dom Krystyny Jandy w Milanówku koło Warszawy był ostatnim przystankiem dla wielu pacjentów i lekarzy wyrzuconego Szpitala Ujazdowskiego.